|

FREDERICK TURNER _________________

THE REAL GAME OF THRONES

___________________________________

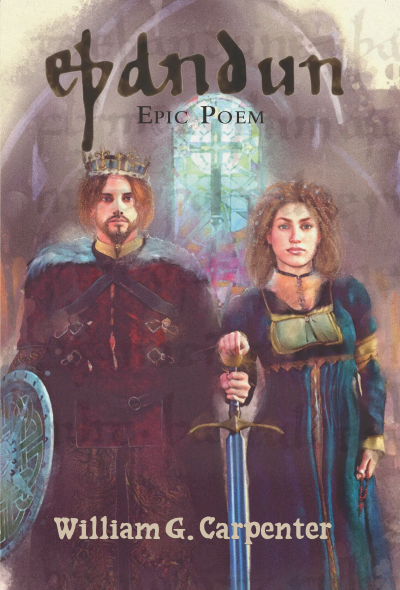

Think of those dark age and medieval illuminated manuscripts, the thickly clotted detail on buckles, brooches, helmets, lamps, tapestries, the return to idiosyncratic and runic content after the centuries of abstract classical form. Even the Romans, as the republic dwindled into the past, were returning to thick narrativity: Trajan's column is a crowded mass of symbolic detail. As papyrus became scarce, expensive parchment made a cost-effective piece of writing dense with meaning. The Bible's wild variety of forms required four distinct levels of interpretation to make it plausibly the word of God. Look at the Book of Kells with its intricate labyrinths, the Bayeux tapestry with its multilingual emblemology. Such works require a different sort of reading, in which a page should take about as long to digest as it took a scribe and illuminator to sweep out and embroider the letters by candlelight. Bill Carpenter's epic--gorgeously illustrated by Miko Simmons--requires and richly rewards such a reading. Carpenter is in some ways the consummate scholar of that period toward the end of the ninth century when Alfred the Great began the history of the English-speaking peoples. His poem deals with the events leading up to the climactic battle between Alfred's army of Wessex and Guthrum's Viking army from East Anglia in the spring of 878. Carpenter is more than a scholar--he is a poet who has utterly disappeared into another time and place and become a learned native there. He reads like a poet of that time, not this one. Some of us today like exploring the earth on Google Earth, never sated with its wealth of detail and deliciously alien landscapes. The lucky among us get to live different lives, speaking a different language, taking part in the local economy and politics. It is not the same as flying above a place in a plane or zipping though it on an autobahn. Experiencing this poem is like such an exploration; it takes a different kind of reading. It needs all the sidenotes, biographical sketches, glossaries, dictionaries and maps that the book provides. It's not like a picture that the eye can take in all at once, but a whole Pompeii whose every corner gives, on inspection, further significance; a wide landscape, an ecosystem where we shiver in a different wind: The pair of pilgrims paced

the wintry downs, The fellows’ features

roughened and grew lean This landscape is the place where Alfred makes his crucial decision to go to Rome and from there to take up his final role as Christian King. But this is not the complacent Christianity of our own times, but a struggle fought out in the landscape itself, an illocutionary moment in the playing-out of the cosmos. Many historical epics give coy sidelights from the time of their composition, and we get acquainted with the author and are invited to make modern judgments on the more primitive choices of the protagonists. Carpenter though is invisible. The poem makes no judgments but such as might have been made by a sophisticated poet of, say 900 AD. Even its vocabulary is singularly lacking in words that descend from Norman and Parisian French: William the Conqueror has not yet arrived. It's basically Anglo-Saxon and North Germanic, with a rich Christian foliage of terms with medieval Latin roots. Though richly idiomatic, there are almost no modern idioms even from educated colloquial American English. This is the birthplace of the English language, the first encounter between Germanic and Latin, the reuniting after 5,000 years of two great branches of Proto-Indo-European, each with its own set of mythologies, lifestyles, moral and legal systems, pantheons, and kinship priorities, all inflamed with what was for them the new revolutionary ideas of Judaic Christianity. So the poem is an investigation of the roots of its own means of expression. The universe of the poem is a few thousand miles across, with the Lord of Hosts above, a pit of groaning sinners below. It began three thousand years ago, and a promised apocalypse could come at any time. It is a different England, subjectively as big as North America in terms of ease of movement and communication. Battles take place between nations that that take twenty minutes today to cross on a motorway. Europe is a whole universe, but without border controls or accurate small-scale maps or official dictionaries or police. It is a natural ecosystem as relatively untouched as Alaska is today. The bloodlines of its folk carried not only the taint and alcohol of original sin, but the mana of great ancestors, pumped with the male seed of warriors into the fertile wombs of haughty princesses and bearing the intended destinies of divine purpose. All events are known and interpreted in realtime as the epochal confluence of many stories and whole cosmologies. God is still fighting it out with other gods, and the significance of the gospels hangs in the balance. We get the feeling of a life lived in the immediate presence of God and his real rivals. But the actors in Carpenter's world are not naive--they are fully as aware, as capable of irony and skepticism, as humanly sympathetic, as politically savvy and economically thoughtful as anybody today. The reader is continually impressed by the huge multilingual learning and historical awareness of the actors. The quiet pleasure of many of our own time's writers at their own greater intelligence and insight relative to their fictional puppets is quite absent. In truth, we are far more the puppets of our ancestors than they are of us. The poem takes work. It is full of loving detail that one must patiently visualize, an exercise that shapes the reader's brain into the receptor of a different world. The poem takes Homer's and Virgil's epic similes and extends them further with Nordic kennings and clerkly digressions, and we must have patience with them, for their wanderings illuminate in more than one sense the core meanings of the poem. Not that the poem is dry scholarly antiquarianism. Its violent mixture of brutal physical realism and exquisite refinement is shocking: “Grandfather Grim,” the

seed of Ingeld growled, As if the Lord had dulled

his sinful will So unlike rigorous Ingwar,

who broke open Read it aloud. This is a poetry that is oral as much as literate, that takes its time and is not interested in economy. It's not easy, but neither is cross-country hiking in new territory. And it is new: our own past is a hundred times more

alien than the present of the most remote tribal landscape of the

present day. And yet it's an alienness in our own linguistic, cultural

and historical blood. We discover the roots of our own ethical

automatisms in Eϸandun’s journey. ________________________________________

|

Eϸandun,

an epic poem

Eϸandun,

an epic poem  Frederick Turner is the winner of the annual Levinson Prize,

Frederick Turner is the winner of the annual Levinson Prize,