|

Joseph S. Salemi

SWINBURNE: THE POETICS OF PLEASURE AND PAIN

_________________

Swinburne was born in London, but most of his childhood and early youth was spent equally at an ancestral estate in Northumberland and another family home on the Isle of Wight. His father was a high-ranking naval officer and his grandfather was Sir John Swinburne, a baronet, parliamentarian, and patron of the arts. His mother came of the titled aristocracy. He was privately tutored, and then attended Eton, followed by Balliol College at Oxford. Swinburne’s earliest publications were blank-verse plays on historical and classical subjects, but he came to real prominence with the appearance in 1865 of his Poems and Ballads, a work that was a true succès de scandale. He was attacked vigorously for some of the more shocking poems in the book, but their beauty was undeniable and their lilting rhythms infectious. By the time Swinburne was thirty, his reputation as a significant poet was assured. Although condemned publicly for the suggestive licentiousness of certain poems, he was avidly read by Victorians who chafed under the moralistic pieties of their time. Swinburne is generally known for four things: an anti-Christian neopaganism, a visceral hatred of political and religious authority, a very delicate skill in both metrics and rhyming, and sadomasochistic proclivities. His radicalism was outspoken, and he was expelled from Oxford for publicly defending an attempt at political assassination. He was of a mercurial disposition and quarrelsome, and late in life had a major row with the painter Whistler. One unfortunate habit of the poet, however, was his tendency to write at tedious length. Swinburne’s collected poems, in the standard edition published in 1904 by Harper & Brothers, run to six fat volumes in small type. Even his best poem, “Dolores,” goes on for fifty-five stanzas. “Laus Veneris” is made up of 106 AABA Rubaiyat quatrains; “Anactoria” has 304 lines; and the “Hymn to Proserpine” runs for 110 hexameters with medial and final rhyme. There are wonderful passages in all of these poems, but they are overwhelmed in a flood of repetitive bombast. Great length in poetry is understandable if one is writing in a straightforward epic or narrative or satiric genre. But Swinburne would seize upon an idea, image, or conceit and develop it endlessly and elaborately, like the recurring motif in a symphony. He was disinclined to turn off the spigot of copia. Nevertheless, let’s look at some of his work. It can be of absolutely stellar quality. The dazzling “Sapphics,” a poem of unearthly beauty, is a good place to begin. It is composed of twenty perfect Sapphic quatrains on a vision of the goddess Aphrodite that came to the speaker during a sleepless night. I can only quote the first six: All

the night sleep came not upon my eyelids, Then

to me so lying awake a vision Saw

the white implacable Aphrodite,

Feet, the straining plumes of the doves that drew her,

Heard the flying feet of the Loves behind her So

the goddess fled from her place, with awful These quatrains are both majestic and eloquent—the sort of work that a poet might give his right arm to produce. Their poetic force and beauty lie in the careful interplay of Anglo-Saxon and Latin derivatives. Notice that the first quatrain is almost totally Germanic in its diction, with only the word “unclosed” being of partial Latin derivation. But the next five quatrains make use of ten perfectly placed Latinate words: vision, implacable, unsandalled, reluctant, straining, plumes, reverted, sudden, clamour, several. These derivatives help establish the stress pattern of the hendecasyllables, but in addition they tend to emphasize strength, movement, and force. Along with the Greek names Aphrodite, Lesbos, and Mytilene, they produce what might be called a tableau vivant of the birth and rising of Aphrodite from the sea foam, in her chariot drawn by doves. Another thing to be noted is eight instances of deliberate doubling of words in five out of the six quatrains (not-not and nor-nor in the first; touched-touched and vision-vision in the second; saw-saw-saw in the third; looking-looking and back-back in the fourth; and thunder-thunder in the fifth). This drumbeat of repetition adds a potent insistence to the theme of “Sapphics,” which is the rebirth of a pagan divinity who comes back to the world with all her force and majesty. Illustrations of Swinburne’s neopaganism are usually taken from his “Hymn to Proserpine,” which is thematically linked to the fourth-century proclamation of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire. The poem carries the epigraph Vicisti, Galilæe (“You have conquered, Galilean”), supposedly the deathbed words of the last pagan Roman emperor, Julian the Apostate. The poem can be read as a dramatic monologue in the voice of Julian: Thou

hast conquered, O pale Galilean; the world has grown grey from thy

breath; Here we see Swinburne’s view that Christianity is a death-oriented religion that renders life pallid and joyless. He carries his attack further by denigrating the Virgin Mary via comparison with Venus/Aphrodite, the Graeco-Roman goddess of erotic love born from the sea foam: Of

the maiden thy mother men sing as a goddess with grace clad around; The Romans claimed Venus as a tutelary deity for their race and city. Venus is here proclaimed as a bountiful queen, while the Virgin Mary is dismissed as a sorrowful slave. Naturally this poem and others in the same vein were highly offensive to some readers, and made Swinburne a controversial figure in his own day. Swinburne could shock not just religious sensibilities, but also moral proprieties. His “Faustine” is a lengthy piece on the Roman empress Faustina the Younger, wife to Marcus Aurelius the Stoic. Unlike her husband, Faustina (according to some ancient sources) was enslaved to the basest passions—a serial adulteress, a poisoner, and a political conspirator. She died under mysterious circumstances in Cappadocia, in the backwash of a short-lived revolt against Marcus Aurelius. Whether these various charges against her are true or not makes no difference to our analysis of Swinburne’s poem—for him, Faustina was an image of female criminality and turpitude. The poem itself is remarkable in its structure. It is made up of forty-one quatrains (rhyming ABAB), of which the first and the third lines are tetrameters, and the second and fourth are dimeters. But line four in every quatrain ends with the name “Faustine,” and line two is a perfect rhyme for the name in all but fifteen cases, where the off-rhyme of —in is employed instead. Swinburne was famous for his ability to maintain perfect or near-perfect rhyme over an extended stretch of verses, and “Faustine” is a specimen of this skill. Look at the first two quatrains: Lean

back, and get some minutes’ peace; The

shapely silver shoulder stoops, The poem goes on to describe how God and Satan played at dice to win the soul of Faustina, and how Satan won, taking the girl as his special minion and confederate in sin: A

suckling of his breed you were, You

have the face that suits a woman You

could do all things but be good Even

he who cast seven devils out Did

Satan make you to spite God? The rest of the poem develops this horrific image of a sex-driven, murderous, and criminal woman whose beauty and sensuality are used only for animal satisfaction and self-advancement. Swinburne describes the empress as a “love-machine,” whose sexual abandon is purely reflexive and loveless: You

seem a thing that hinges hold, Not

godless, for you serve one God, This last quatrain would have been particularly shocking to classically educated Victorians. The Lampsacene god is Priapus, the minor divinity with a huge and prominent erection who served as a scarecrow in gardens, and whose “rod” (the erect phallus) was an emblem of male lust and fruitfulness. Here Swinburne suggests that Faustina’s only lord and god was the aroused penis—a judgment that many learned Victorians would have perhaps shared, but would have balked at putting into cold print. Concerning Swinburne’s penchant for sadomasochism, the best evidence is his holographic folio manuscript The Flogging-Block: An Heroic Poem, which he kept working on and adding to for nearly twenty years, and which was only published in 2011, after being sequestered among the Ashley Manuscripts in the British Library. It is over 42,000 words in a variety of poetic forms, but solely focused on the pains (and silent pleasures) of having one’s bare buttocks savagely whipped by teachers at Eton with a wide range of rods, sticks, or branches. It is divided into sections called “Eclogues,” which maintain a sketchy kind of dramatic sequence, and one of the main characters is a boy named Algernon. He and his companions go through all sorts of whippings or floggings, described in lurid detail as regards the pain, the bleeding, the terror—and, of course, the unspoken fascination that both boys and teachers had with the entire process. The poem is relentless in its barely concealed sexual obsessions, but a sample should be given:

Don’t you know you’re complained of—by Armstrong? Oh, yes! The “horse” mentioned at the end of this passage refers to the infamous “birching-stool” or “flogging-block” of Eton: a pair of wooden steps on which guilty students were compelled to kneel and bend over while their bare buttocks were smartly whipped with a strong but supple branch. The branch (which had been soaked in brine) was studded with hard emerging buds that would frequently cut the skin. “Riding the horse” meant to be whipped. This punishment was so common in English public schools that an unnatural taste for whipping and being whipped developed in many boys, who carried the proclivity over into adult life, and into their sexual relationships in general. The French phrase le vice anglais became common on the Continent as a shorthand for the tendency of Englishmen to want to whip the bare buttocks of their sexual partners, and to be similarly whipped in turn. That Swinburne was enamored of this practice is no longer in doubt, though in his poems it often appears in a somewhat sublimated form as a general fascination for eroticism tinged with pain and some blood. But let’s turn to his magnificent poem “Dolores,” which has as its parenthetical subtitle Notre-Dame des Sept Douleurs (Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows). It probably shocked Victorian readers more than any other of Swinburne’s pieces. Close friends urged him not to include it when the first edition of Poems and Ballads was being readied for the press. The poem is a paean to the prostitute as a mystical counter-icon to the Virgin Mary, with “Our Lady of Pain” as a bob-line at the end of many of the stanzas. The poem is an amazing conflation of Swinburne’s sexual frankness, his fascination with the prostitute as an idol of sensuality, his contempt for Christian moral restrictions, and his personal taste for erotic pleasure that carries a sting of pain. The first fifteen stanzas are very powerful: Cold

eyelids that hide like a jewel

Seven sorrows the priests give their Virgin; O

garment not golden but gilded, O

lips full of lust and of laughter, In

yesterday’s reach and tomorrow’s, Who

gave thee thy wisdom? what stories We

shift and bedeck and bedrape us,

Fruits fail and love dies and time ranges;

Could you hurt me, sweet lips, though I hurt you?

There are sins it may be to discover, Ah

beautiful passionate body As

our kisses relax and redouble, Hast

thou told all thy secrets the last time, By

the hunger of change and emotion, By

the ravenous teeth that have smitten On it goes, for another forty stanzas. To modern taste such verse may seem rhetorically overblown, artificially languorous, and too lush with description. But for Swinburne’s time, it was daring and provocative. The subject matter itself would have been indecorous to Victorian tastes, but even more shocking would have been the honest sensuality of the language. The prostitute is depicted here not in the stereotypical, moralizing manner of nineteenth-century disapproval, but as a fascinating erotic goddess: voluptuous, wise, carnal, divine, poisonous, privy to vile desires, and irresistible. She is sinful, but her sins are a fountain of unholy passions and forbidden delights. For Swinburne, the blending of pain and blood with sexual perversity and pleasure was inevitable, and this mixture is the key to any sophisticated reading of “Dolores.” As a

scholar I find it annoying that there are still some dimwitted critics

in academia who resist admitting that “Dolores” is a poem about the

prostitute and prostitution. You find some persons desperately trying to

argue that the poem deals with “the eternal Feminine,” or Aphrodite, or

with some symbolic archetype, or with a libertarian protest against

sexual strictures. But frankly, you have to be profoundly stupid or

willfully blind to read “Dolores” without noticing the direct references

to commercial sex. The words “Hard eyes that grow soft for an hour” or

“O garden where all men may dwell” or “house not of gold but of gain” or

“barren delights and unclean,” or “Things monstrous and fruitless” all

evince Swinburne’s intention to write about a whore—a The same critical distortion haunts feminist treatment of Swinburne’s poem “Anactoria,” a dramatic monologue in the voice of Sappho. It is based on a short poem of Sappho about love, which mentions a desired girl (Anactoria) as absent. Swinburne takes this Greek original as the inspiration for a lengthy monologue by Sappho to the absent girl, berating her for infidelity, wishing her dead, complaining bitterly about rivals, fantasizing about cannibalistic sexual violence, and reveling in the prospect of her own literary immortality. It has its beautiful moments, but is essentially an unpleasant poem that reveals Swinburne’s obsession with sex and pain, along with Sappho’s unreasoning lust for a girl and her insatiable hunger for fame. And yet the standard feminist reading of this poem is that it is a triumphant statement of lesbian love and female liberation. Once again, political commitments dictate a false reading of Swinburne’s actual text. Here is a sample from “Anactoria” to show how Swinburne’s sadomasochism permeates the poem: Ah

that my lips were tuneless lips, but pressed “Anactoria” is certainly not a poem about any conceivable variety of healthy love. It is about homoerotic perversion that builds to a crescendo of violence and cannibalism. But since it is in the voice of their heroine Sappho, brain-dead feminist critics must read it as a triumphant celebration of female empowerment. There is much more in Swinburne that cannot be discussed in the space of this essay. His translations from Villon, his many verse dramas, his beautiful roundels, his highly tendentious political poems, his Arthurian epyllion Tristram of Lyonesse… there seems to be no end to the man’s poetic output. The Muse that drove him was insistent and untiring. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature several times, and thrice he lost to nonentities—probably because of tight-assed Swedish discomfort with his reputation as a poet of unsavory subjects. He was also a substantial literary critic who produced studies on Shakespeare, Jonson, Blake, Charlotte Bronte, Victor Hugo, and others. Swinburne was an example of something that is rapidly disappearing in our world: a passionately serious man of letters. His poetry, despite its violence and irreligion and contentiousness, is of the first rank

___________________________________

Joseph S. Salemi has published poems, translations, and scholarly articles in over one hundred journals throughout the United States, Canada, and Great Britain. His four collections of poetry are Formal Complaints and Nonsense Couplets, issued by Somers Rocks Press, Masquerade from Pivot Press, and The Lilacs on Good Friday from The New Formalist Press. He has translated poems from a wide range of Greek and Roman authors, including Catullus, Martial, Juvenal, Horace, Propertius, Ausonius, Theognis, and Philodemus. In addition, he has published extensive translations, with scholarly commentary and annotations, from Renaissance texts such as the Faunus poems of Pietro Bembo, The Facetiae of Poggio Bracciolini, and the Latin verse of Castiglione. He is a recipient of a Herbert Musurillo Scholarship, a Lane Cooper Fellowship, an N.E.H. Fellowship, and the 1993 Classical and Modern Literature Award. He is also a four-time finalist for the Howard Nemerov Prize. His upcoming book, Gallery of Ethopaths, is forthcoming from Pivot Press. |

|

|

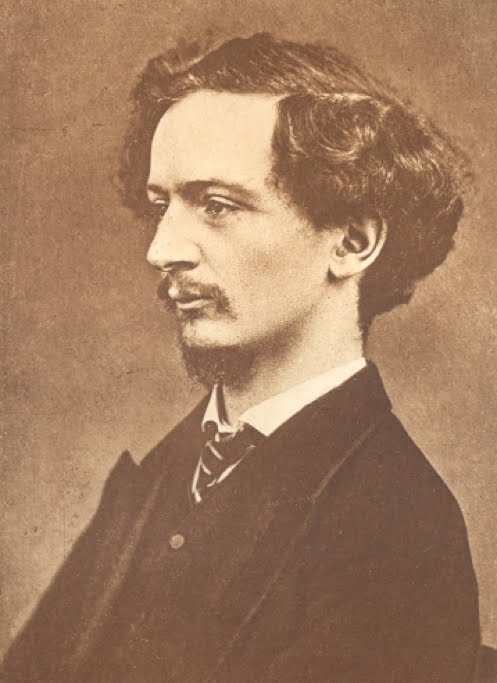

Algernon

Charles Swinburne (1837-1909) has the triple distinction of being a

Romantic, a Victorian, and a Decadent. His work is as lushly florid as

Keats and Shelley, as long-winded as Tennyson, and as fin de siècle as

Wilde or Dowson. He even has a good claim to be a Pre-Raphaelite, for he

was well acquainted with and influenced by the Rosettis, Burne-Jones,

and several other members of that group. Swinburne is often thought of

as an important transitional figure between nineteenth-century

conventionality and the less restrained subject matter of early

twentieth-century poetry.

Algernon

Charles Swinburne (1837-1909) has the triple distinction of being a

Romantic, a Victorian, and a Decadent. His work is as lushly florid as

Keats and Shelley, as long-winded as Tennyson, and as fin de siècle as

Wilde or Dowson. He even has a good claim to be a Pre-Raphaelite, for he

was well acquainted with and influenced by the Rosettis, Burne-Jones,

and several other members of that group. Swinburne is often thought of

as an important transitional figure between nineteenth-century

conventionality and the less restrained subject matter of early

twentieth-century poetry.