|

Joseph S. Salemi _________________

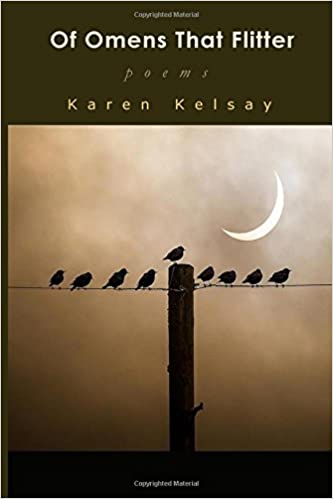

A GOOD OMEN

___________________________________

Boston: Big Table Publishing, 2018 ISBN: 978-1-945917-26-4

Karen Kelsay is something of a one-woman dynamo in the poetry world. Apart from her seven published books (this one makes eight), she is well known as the motivating force behind Kelsay Books and the White Violet Press, the on-line journals Orchards and Victorian Violet, and for her many published poems in both hard-copy and on-line journals. The acknowledgments page in this new book lists forty-one small magazines, and her work has also been anthologized frequently. In addition, she is the recipient of six Pushcart Prize nominations. In Of Omens That Flitter, the journal with the largest amount of material sourced is TRINACRIA, with twelve poems, including the title piece. It is gratifying to see TRINACRIA’s choices represented this heavily, taking pride of place, as it were, in Kelsay’s collection. But not all of the poems in her new book are formal; there are several free-verse items as well. The author’s versatility in both modes is amply demonstrated, and it is proper to note here that Kelsay’s unpatterned poems are not the usual amorphous dreck that dominates mainstream poetry. The free verse here is as carefully done and as polished as her tight sonnets. Kelsay’s primary strength as a poet is that of cool and detached observation—the ability to focus on something intensely and to describe it and comment on it in precise and limpid language. One doesn’t get impassioned outbursts or argumentation or blurry impressionism or splashes of unexpected rhetoric from a Kelsay poem. Instead each poem comes across as a perfect snapshot taken by a professional photographer, and then pressed carefully into an album. This kind of controlled perception funneled into crystalline and grammatically non-problematic English has become a hallmark of Kelsay’s style, and sets her apart from the mass of emotion-mongers who parade their wounded psyches in most magazines today. One of the early achievements of New Formalism as a movement was the rediscovery of the quatrain as a basic building block, whether used traditionally as a component of a larger fixed form, or simply as a regularized break in a longer piece. The quatrain (as Kelsay shows here) can have a number of rhyme schemes: ABAB, ABBA, AABB, xAxA, or even monorhyme. And an important related development in New Formalism was the freedom to use enjambment from one quatrain to the next, without any kind of pause in word flow. This practice was often considered a fault in the past, or at least something to be tolerated only occasionally. A number of poets showed that enjambment from quatrain to quatrain was perfectly natural. Karen Kelsay is especially good with the quatrain, and her ability to enjamb the syntactic flow from quatrain to quatrain can be seen in her sonnet “Winter in England,” which begins this way: It’s here I pause with

each December, where glossing of frost. It’s here I garner all… This enjambment continues through the poem, right to the close. There are six sentences in the sonnet, but only one period coincides with a line’s ending. Such a thing isn’t easy to pull off, but when it is done the reader experiences both the regularity of rhyme and meter, and the freedom of unfettered speech. And it is only possible when the poet has an absolute grammatical and syntactical control of the language. Kelsay’s descriptive skills are well-honed, but if that were her only talent she would not be much different from a hundred other poets. What makes her stand out from the crowd is how her descriptions are employed to create vivid scenarios of personal reminiscence or literary allusion. Two poems of this nature are “La Sierra 1946” (which recalls a school at the distance of sixty years), and “Lady of Shalott” (based on the Arthurian legend as revisited by Tennyson). In the former poem we are given brief mentions of remembered architectural items (“colonnade,” “rectangle chapel,” “plaster walls,” “dormitory stairs”) as part of a “fight…to capture every yesteryear you’ve owned.” In the latter piece, the same technique is at work: French tapestries,

embroidered with spun gold, But here the poem goes on to evoke the Tennysonian story of chimes, windows, the mirror, the unfinished canvas, and the image of Sir Lancelot. It is allusive in the best sense of the word—the poet assumes a reader’s familiarity with an earlier text, and then touches on the most salient points in contemporary language. Kelsay can also use allusion to comment on a totally separate subject, as she does in “The Tortoise and the Hare.” Only the title makes any direct reference to the Aesopian fable; the entire poem is a meditation on which of her aging parents will win the race to death. Kelsay usually does not write on personal matters, and this poem is therefore something of a surprise in a collection that is overwhelmingly impersonal and somewhat distant. But even in her fiercely fixated and cool descriptions Kelsay can give glimpses of her own feelings, as in the magnificent sonnet “The Courtship Hour,” which was printed in TRINACRIA. There is no need to quote it here; all I can say is that the poem’s description of twilight, quiet, a bed, oncoming sleep, along with the merest hint of lovemaking, is masterly. A perfect poem such as this is something that one might labor years to compose. One of Kelsay’s signature skills is the ability to choose an object, describe it in context, and then conjure up personal memories or a generalized nostalgia. “Solace from a Pasture Gate” and “Thoughts on a Step” are prime examples of this procedure, but a tour de force is the perfect six quatrains that make up “In a Hat Box.” The first half of the poem meticulously itemizes the contents of an old box, while second half expands this description into a reminiscence on the early life of her mother. It all fits together, like the weave of a seamless robe, and Kelsay again makes excellent use of enjambment from quatrain to quatrain to ensure the smooth flow of language. This is a fine collection by an undeservedly neglected poet—but what else is new in a po-biz world enamored of garbage art? The excellent work of Kelsay will have to be its own reward, cherished by a small group of appreciators. I like to think that the publication of a book as charming as this one is in itself a good omen of the slowly percolating counter-revolution against modernist imbecility. Let’s hope Karen Kelsay continues to enchant us with work of this caliber.

Joseph S. Salemi has published poems, translations, and scholarly articles in over one hundred journals throughout the United States, Canada, and Great Britain. His four collections of poetry are Formal Complaints and Nonsense Couplets, issued by Somers Rocks Press, Masquerade from Pivot Press, and The Lilacs on Good Friday from The New Formalist Press. He has translated poems from a wide range of Greek and Roman authors, including Catullus, Martial, Juvenal, Horace, Propertius, Ausonius, Theognis, and Philodemus. In addition, he has published extensive translations, with scholarly commentary and annotations, from Renaissance texts such as the Faunus poems of Pietro Bembo, The Facetiae of Poggio Bracciolini, and the Latin verse of Castiglione. He is a recipient of a Herbert Musurillo Scholarship, a Lane Cooper Fellowship, an N.E.H. Fellowship, and the 1993 Classical and Modern Literature Award. He is also a four-time finalist for the Howard Nemerov Prize. His upcoming books, Gallery of Ethopaths, and a collection of critical essays, are forthcoming. |

Karen

Kelsay,

Karen

Kelsay,