|

Joseph S. Salemi DR.

SAMUEL JOHNSON:

THE POETRY

OF A PROSE

STYLIST

_________________

He is disliked today (and consciously disregarded by a politically correct academia) because he was a solid Tory who made no bones about his views or his attitudes. An anecdote is told that once when Johnson conversed with a liberal, he dismissed the man with these trenchant words: “Sir, I perceive that you are a vile Whig. Good day.” If only we had more tough-minded persons of that kidney nowadays! Johnson was a rock of certitude, and he did not tolerate fools. Johnson’s greatest achievements are in the realm of prose. I think it no hyperbole to say that he single-handedly established the criteria for decorous and proper writing in English; and without his example our language would never have attained the level of excellence, precision, lucidity, and sharpness that have been the signs of carefully written English since the end of the eighteenth century. Other writers could compose as well as he did, but it was Johnson—with his torrent of first-rate essays and commentaries—who set the standard that has always been used by our best prose stylists. Nevertheless, in this brief portrait I propose to deal exclusively with his English poetry, as I have done with my other subjects of study. Johnson was born in Staffordshire, the son of a humble bookseller. As an infant he was sickly, and was not expected to live long. But he survived several bouts of illness, and soon developed into something of a child prodigy, with an uncanny ability to memorize and recite long passages of prose and verse easily. He was skilled in Latin by the age of six, and by the time of his fifteenth birthday he was composing excellent verse in both Latin and English. At nineteen he matriculated at Pembroke College, Oxford. Johnson mastered both French and Greek during his short time at university, but his family’s poverty compelled him to leave without taking a degree, after less than two years of study. Although Johnson was a man of letters right down to the marrow of his bones, he took a rather hard-boiled stance towards the writing profession in general. He is famous for the wry remark that “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.” He was never totally secure financially, and often composed under the pressure of deadlines and need. His famous (and highly popular) moral apologue Rasselas was composed in a week of furious writing, as a way to earn money to pay for his mother’s funeral expenses. In a world where copyright protections were minimal and authors often worked for simple fixed fees, Johnson always had to be ready with his pen. Let’s take a look at a poem of his that touches upon his somewhat cynical view of an author’s predicament. Here is the beginning of his poem “The Young Author,” written when he was still quite new to the profession:

When first the peasant, long inclin’d to roam, Johnson seems to have been exasperated by the feeling that his work was never fully appreciated or rewarded. His embittered response to the Earl of Chesterfield, who gave support for Johnson’s great dictionary project only when the task was nearing completion, is well known. Like many writers, Johnson was touchy on the subject of his merits, and took lack of recognition badly. Here’s a passage from his “London: A Poem,” wherein the speaker talks of that city with disgusted contempt:

Since Worth, he cries, in these degen’rate Days,

Johnson was subject to deep bouts of depression and melancholy, no

doubt aggravated by his sense that his literary merits were either

ignored or taken for granted. This ingrained pessimism is apparent in

almost all that he wrote, most vividly in his most celebrated poem, “The

Vanity of Human Wishes.” This 368-line excursion in perfect heroic

couplets takes its inspiration from the bitter tenth satire of Juvenal,

a Roman author whom Johnson favored. The ancient Latin satire ranges

over many human curses: our failure to distinguish good from evil; the

dangers of wealth; the snares of power, eloquence, and military glory;

the cares of old age; the transience of beauty. It ends with a stoic

plea for endurance, courage, the suppression of our passions, and manly

fortitude and virtue. Johnson follows this model, but enfleshes his poem

with instances and examples drawn from his own time—in particular the

world of London—and he avoids the intense rancor that Juvenal exudes.

Johnson begins his poem with a somewhat detached and philosophical tone, in the phlegmatic manner characteristic of an Englishman:

Let Observation with extensive View, Johnson felt keenly the tyrannical power that gold wielded in London, the mercantilist capital of the nascent British empire. Surrounded by avarice, social-climbing, the temptations and intrigues of the royal court, the machinations of corrupt politicians, and a city in the grip of lucrative international commerce, he could not help thinking of the Latin dictum Auri sacra fames quid non? (“O cursed hunger for gold, what will you not do?”) Here is his judgment in the poem:

But scarce observ’d the Knowing and the Bold, London in Johnson’s day was the central locus of British power, with King, Parliament, courts, military, high society, fashion-and-luxury industries, and a robust body of merchants and shippers turning the city into a hotbed of acquisitiveness, display, and status-seeking. Johnson’s description of the place is vivid, but contemptuous:

Unnumber’d Suppliants croud Preferment’s Gate, These longer poems of Johnson give readers the picture of a solemn authority figure, one who is aloof, derisive, condemnatory, and somewhat cold. Johnson could indeed be of that ilk, as his biographer Boswell notes in many anecdotes and quotations. And as a serious satirist, Johnson was bound to come across as rather stern and magisterial. And yet not all of his poetry is of that nature. He could be complimentary and gentle, as in “To a Young Lady on her Birthday,” as these first six lines show:

This tributary verse receive, my fair, In fact, many of Johnson’s poems are addressed to women—always in the courteous and highly laudatory manner of one who realizes he can expect very little from them by way of romance. He married a well-to-do widow twenty-one years his senior, probably out of financial necessity. When his wife died, he spent many years of chaste devotion to the wealthy Mrs. Thrale, only to be dumbfounded and disappointed when she married someone else after her husband’s death. Johnson was not suited for love. He had many health problems throughout his life—scrofula, gout, dropsy, asthma, and a variety of other lesser afflictions that left him disabled and convalescent for long periods. He was tall, but prone to stoutness, and suffered from some nervous tics. His appearance and disposition were not of a nature to endear him to the ladies, and he was well aware of it. But he was unfailingly gallant to them in his verse. There is a wistfulness in this poem written to Miss Hickman, the eighteen-year-old daughter of an early benefactor:

Bright Stella, form’d for universal Reign, The name of Stella was a standard poetic pseudonym used by poets of that time to address a real or fictional love (along with many other feigned names, such as Delia, Phyllis, Laura, Cynthia, Thalia, and the like), and he uses it in several poems. Johnson may not have meant any actual woman, but just an ideal or imagined love. In the following poem (“The Winter’s Walk”), he combines his typical pessimistic gloom with a wish for the relief of feminine comfort and solace:

Behold my fair, where-e’er we rove,

Nor only through the wasted plain,

Enliv’ning hope, and fond desire,

In groundless hope, and causeless fear,

Tir’d with vain joys, and false alarms, No essay on Johnson’s poetic ability would be complete without consideration of the man’s prodigious skill in translation. He could handle not just Latin and Greek, but also French, Spanish, and Italian. One testament to this fluent linguistic gift is his English version of Joseph Addison’s Latin poem Pygmaiogeranomachia (“The Battle of the Pygmies and Cranes”). Johnson completed the 170-line translation in 1726, when he was a student of seventeen at Stourbridge School in Worcestershire. Here’s the beginning:

Feather’d battalions, squadrons on the wing How many seventeen-year-olds can write heroic couplets that sophisticated? None today, I suppose—but even in Johnson’s better-educated times the skill must have been a rarity. More remarkable is the fact that the young Johnson took a non-rhyming Latin poem and rendered it into mellifluously rhyming English. Johnson’s long translations from Horace, Virgil, Boethius, and Euripides are just as polished and satisfying, but I would like to present a few of the countless snippets of classical verse that he would include from time to time in his essays in The Rambler as epigrams or mottoes. I’ve prefaced each with the original Latin, followed by a literal English translation of my own, and then Johnson’s rendering:

1) Terra salutiferas herbas, eademque nocentes, (Earth nourishes health-giving plants, and also harmful ones, and the rose is often near the nettle.)

Johnson: 2) Caelum non animum mutant. [from Horace] (They change their sky, not their spirit.)

Johnson:

3) Nulla fides regni sociis, omnisque potestas (There is no trust in rule with allies, and all shared power will be unendurable.)

Johnson: Notice how perfect, how apt, how completely felicitous each of Johnson’s renderings is! He captures the essential meaning of the Latin original, and at the same time produces an English version that is as natural and fluent as a sylvan brook. Many a poet has been a faithful translator, but only a gifted few have this capacity for producing an effortless and seamless metamorphosis from one language into another. Johnson’s one dramatic work, the play Irene, was a modest success, and was produced by David Garrick in 1749 at a Drury Lane theater. It is mostly in blank verse, with some rhyme scattered here and there. I can only quote one speech by the heroine as a sample of its style:

Ambition is the Stamp impress’d by Heav’n These are stately, marmoreal verses, strongly magisterial and didactic. They are not quite the thing we expect from a female character. But they do reveal Johnson’s sturdy, solid, conservative, moralistic side. He never could totally lay aside that element of his personality, which permeates almost everything he wrote. But I would like to end by quoting a surprisingly different kind of poem, written by him in 1776, when he was sixty-seven. It is “To Mrs. Thrale on her Thirty-Fifth Birthday.” Johnson’s relationship with Hester Thrale has been discussed endlessly, but what is indisputably evident is his deep devotion to her, his pleasure in her company, his dependence on her and her husband’s steady hospitality and support, and his utter desolation over their broken friendship after her second marriage to Gabriele Piozzi. Despite the great difference in their ages, Johnson felt a closeness to Mrs. Thrale, as this somewhat wistful poem in monorhyme evinces:

Oft in Danger yet alive This is a touching tribute to an honored and close friend, but it also carries an unspoken declaration of something deeper than friendship: an unattainable wish for love, and a profound sense of the inevitable passage of time. The break with Mrs. Thrale, the close of the literary gatherings at her home, and the end of the invitations and dinners that he so loved—these were the backdrop of Johnson’s final, sad, and lonely years. It is said that Samuel Johnson is the second most quoted writer in the Anglophone world, after Shakespeare. Can it be doubted? He published The Rambler from 1750 to 1752, bringing out 208 separate issues. Each issue had a single polished essay, and all but four of them were written by Johnson alone. Every essay is a masterpiece of English prose, and all of them together constitute a treasury of perceptive comment, sound judgment, and moral wisdom. In the last issue, Johnson took leave of his readership with the following words: I have laboured to refine our language to grammatical purity, and to clear it from colloquial barbarisms, licentious idioms, and irregular combinations. Something, perhaps, I have added to the elegance of its construction, and something to the harmony of its cadence. Those are the words of a true giant. His contribution to the majesty, authority, and pre-eminence of the English tongue is no less than that of Cicero to classical Latin, or Dante to Tuscan. His monumental Dictionary set a standard for prescriptive usage that lasted for two hundred years, until the triumph of a debased lexical relativism in the 1960s. We all know Johnson for his elegant and precise prose, but are less familiar with his poetry. I hope we will get to know him as well for his crystalline verse.

___________________________________

Joseph S. Salemi has published poems, translations, and scholarly articles in over one hundred journals throughout the United States, Canada, and Great Britain. His four collections of poetry are Formal Complaints and Nonsense Couplets, issued by Somers Rocks Press, Masquerade from Pivot Press, and The Lilacs on Good Friday from The New Formalist Press. He has translated poems from a wide range of Greek and Roman authors, including Catullus, Martial, Juvenal, Horace, Propertius, Ausonius, Theognis, and Philodemus. In addition, he has published extensive translations, with scholarly commentary and annotations, from Renaissance texts such as the Faunus poems of Pietro Bembo, The Facetiae of Poggio Bracciolini, and the Latin verse of Castiglione. He is a recipient of a Herbert Musurillo Scholarship, a Lane Cooper Fellowship, an N.E.H. Fellowship, and the 1993 Classical and Modern Literature Award. He is also a four-time finalist for the Howard Nemerov Prize. His upcoming book, Gallery of Ethopaths, is forthcoming. |

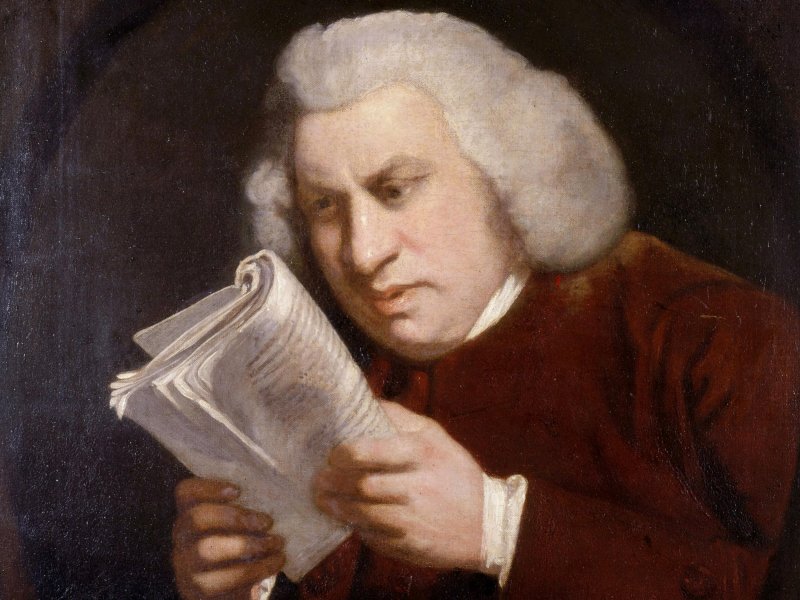

Doctor Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) is a literary and scholarly giant.

In his day he bestrode the English world of letters in much the same way

as T.S. Eliot or Edmund Wilson did in the twentieth century. Besides

being a skilled poet in the Augustan style, he was a perceptive critic,

a gifted translator, a biographer, editor of The Rambler, a novelist and

composer of travelogues, an active journalist and essayist, a writer of

prefaces and political pamphlets, and a playwright—a dazzling array of

activities, all of which are overshadowed by his completion of the

Herculean task of compiling the first truly scientific Dictionary of

the English Language. With Sir Joshua Reynolds, he presided over the

important literary salon called “The Club,” as well as the weekly

intellectual discussions held at the home of Mrs. Hester Thrale.

Compared to the pathetic rabbits that populate our contemporary literary

scene, Samuel Johnson is an eighteen-point stag. His energies were

simply phenomenal, and his achievements matched them.

Doctor Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) is a literary and scholarly giant.

In his day he bestrode the English world of letters in much the same way

as T.S. Eliot or Edmund Wilson did in the twentieth century. Besides

being a skilled poet in the Augustan style, he was a perceptive critic,

a gifted translator, a biographer, editor of The Rambler, a novelist and

composer of travelogues, an active journalist and essayist, a writer of

prefaces and political pamphlets, and a playwright—a dazzling array of

activities, all of which are overshadowed by his completion of the

Herculean task of compiling the first truly scientific Dictionary of

the English Language. With Sir Joshua Reynolds, he presided over the

important literary salon called “The Club,” as well as the weekly

intellectual discussions held at the home of Mrs. Hester Thrale.

Compared to the pathetic rabbits that populate our contemporary literary

scene, Samuel Johnson is an eighteen-point stag. His energies were

simply phenomenal, and his achievements matched them.