|

JOSEPH

HARRISON:

Review by

Robert Darling ______________

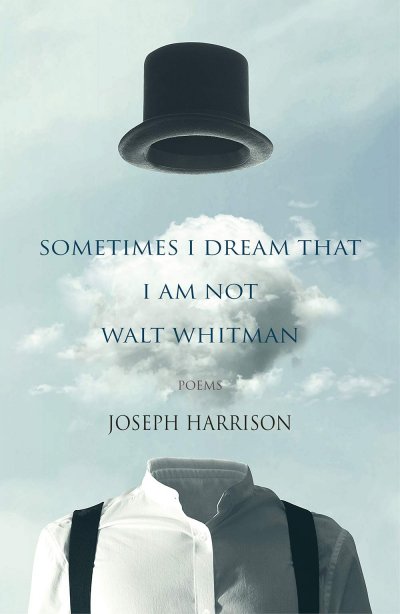

Sometimes I Dream I am not Walt Whitman [Sometimes] is Harrison’s fourth full length collection. (A manuscript from the 1980s was published in 2016 as The Imposition of Ashes and, while still worth reading, is not up to the standards of his mature work. He was also ‘included’ in another volume, The Fly in the Ointment, but more on that later.) Each collection has its own logic, though the voices in them are unmistakably Harrison’s. The plural in the previous sentence is deliberate, for Sometimes... is filled with voices. Indeed, the collection is replete with allusions, and Harrison is a master ventriloquist as well as a gifted poet in his own voice, or voices. One section is given over to the voice of Walt Whitman, another to Emily Dickinson, the two great literary forebears of modern American poetry; in the former sequence Whitman calls on Álvaro de Campos, one of Pessoa’s noms de plume. Also appearing as either voice or subject are Frost, Hardy, Dickens, Strand, Stevens, Swinburne, Shakespeare (at least his head) as well as the painters Giotto, Velázquez, and Cézanne. Harrison prepares the reader with a prefatory poem “River of Song”: Who

said that? The

dead keep singing. They don’t sleep. Art is, in many ways, a dialogue with the dead as much as with the living. Much effort is spent by apprentice poets on developing a voice. Harrison might ask, “Just one?” Harrison is also a master of form, both received and nonce. “The River of Song,” printed above, dealing with echoes, is composed of two stanzas that echo each other. But the poet is also a master of syntax. To cite two obvious examples: “Dickens on Fire” is a poem that deals with the frantic, all-consuming life of activity led by Dickens. The poem consists of eleven stanzas of fifteen lines each. All stanzas are the same form with an intricate rhyme scheme and lines measuring from monometer to pentameter. Through the mad rush of events the poem describes, one notices only in retrospect that the 165 lines are but one sentence. On the other hand, “Late Autumnal,” dealing with the slow fading of the season, has seventeen sentences (admittedly some fragments) in its eleven lines. Harrison’s pacing from poem to poem is superb. Section three deals with matters of more directly topical concern. The blimp in “Runaway Blimp” not only commanded a runaway budget but its “virtues, prematurely celebrated / For scope, precision, instant valence, / Proved much exaggerated”; it escapes from its mooring and has to be brought down in an adjoining state: And

soon they’ll want to know at High Command The “Song of the NRA” has the repeated chorus line of “America I’ve got my gun!: “A firearm doesn’t pull the trigger / Each time a toddler shoots a parent.” “Easter 2016” is a sonnet that actually makes more use of “The Second Coming” than “Easter 1916” to describe the current political madness and the odd fact that many vote against their own best interests: “The harmed are drawn to what would do more harm.” “Coulrophobia with Line from Auden” makes use of “The Fall of Rome” to deal with ecological disaster: “Meanwhile more vulnerable, vast / Networks of ecosystem start / To melt and dry and break apart, / Silently and very fast.” From echoes to ecosystem. For a

book with such a literary flavor, the reader should not be surprised to

encounter a poem, in this case a sestina, satirizing the literary scene.

In “Harvest Hobson,” the hero is a little-appreciated poet who remains

appropriately nameless throughout the poem; the subject is upset by the

great popularity of a rival poet, Harvest Hobson. He writes an essay, a

“wicked assault of withering irony,” entitled “’Harvest Hobson and the

New Pretentiousness.” Unfortunately, the irony is missed (anyone who has

taught Swift’s “Modest Proposal’ to undergraduates can appreciate this)

and he becomes known as the most influential critical champion of

Hobson: “His essay helped secure, for Harvest Hobson, / A major prize.”

Frustrated, he directly attacks Hobson in another essay, which elicits the

public’s considering him... A

snake whose treacherous pretentiousness But the name Hobson has echoes of its own. Another poem in the collection, “Hobson’s Choice,” a somewhat mysterious work, begins: “What needs old Hobson for his broken bones / And girt, his sloughed-off skin? Shifter. . . “. Who is Hobson, this ‘shifter’? Sometimes... is prefaced with a wonderfully apt epigraph from J. H. Hobson’s A Human Touch: The Poetry of William Karl, a book that does not seem to exist. Suspicious. In his forward to Harrison’s first mature full-length collection, Someone Else’s Name-- a bit of a hint there--Anthony Hecht notes that the book’s epigraph from George Puttenham’s The Arte of English Poesie (1589) claims to be from Book IV, chapter ix., whereas Puttenham stopped after Book III. Harrison’s next collection, Identity Theft, another apt title, has no epigraph, while Shakespeare’s Horse has an epigraph from (yes) J. H. Hobson’s Six Days in Buenos Aires, yet another book that does not seem to exist. The only trace I can find of J. H. (Joseph Harrison?) Hobson I can find is as the editor of The Fly in the Ointment, an anthology of a Baltimore poetry performance group that called themselves The Fly and consisted of Barrymore Ashe (some strange melding of Ashberry, Berryman and Wendell Berry?), Joseph Harrison, Frank Hart (a great name for a confessional poet) Vironique, and Stephen Wallace (the philosophical poet of the group—Wallace Stevens?). Joseph Harrison is a shape-shifter over years, committing Identity Theft and using Someone Else’s Name, a poet of both seriousness and fun. Sometimes I Dream that I am not Walt Whitman is unlikely to be widely reviewed or nominated for many prizes—it is probably too literary for an unlettered audience and more concerned with the politics of identity than with identity politics. It is a complex book whose concerns can only be all-too-briefly sketched in a short review. But even though a few months of this unfortunate year are left, I doubt we will see another book in 2020 as good as this one. Indeed, Joseph Harrison is one of our finest poets, and it is high time he’s recognized as such.

|

|

|

Joseph

Harrison

Joseph

Harrison