|

Current

Archives: From December 2013-

We Lose

A Master

Poet

Dick

Allen,

one of

the

three

founders

of the

Expansive

Poetry

movement,

could

not be

fenced

in by

definitions.

He wrote

wonderful

formal

verse,

had a

gift for

short

narratives,

but also

wrote a

funky

epic

nearly

fifty

years

ago (Anon),

where

the

short,

free

verse

lines

fit the

material

so well

that you

could

not

imagine

him

writing

any

other

way.

But, of

course,

he did.

In

Regions

with No

Proper

Names,

the

verse

often

employed

was

vers

libre,

metrical,

but with

varying

line

lengths,

evolved

not only

from the

vers

libre

movements

in

France

in both

Moliere’s

time and

later in

the 19th

century,

but from

the

marvelous

17th

century

English

poet,

Abraham

Cowley.

Allen

kept up

with

everything

in the

field.

Meet him

on a

Monday

for a

reading,

or visit

his

cottage

in

Trumbull,

where he

and Lori

lived,

and he’d

wonder

if you’d

read

half a

dozen

poets

he’d

just

finished

with

that

weekend.

He

didn’t

understand

writers

who

weren’t

immersed

in what

we do as

poets.

Why

bother

if you

aren’t

he

seemed

to say.

He had a

passion

for

verse,

exercised

in at

least

ten

published

books.

His

talent

embraced

criticism

as well,

not only

through

insightful

essays

on

verse,

but in

editing

critical

anthologies

in

science

fiction

and in

detective

fiction.

And

there

was more

as yet

unseen,

including

an epic

written

within

the last

ten

years

that has

yet to

see

publication.

Such

passions

don’t go

unnoticed.

Dick

received

a

variety

of

awards

and

grants

over the

decades,

including

the

National

Book

Critics

Circle

Award

for

Overnight

in the

Guest

House of

the

Mystic,

the New

Criterion

Poetry

Prize

for

Shadowy

Place

and the

Connecticut

Book

Award

for

Present

Vanishing.

He

received

the

Robert

Frost

Prize,

the

Pushcart

Prize,

the Hart

Crane

Poetry

Prize

and

fellowships

from

National

Endowment

for the

Arts and

the

Ingram

Merrill

Foundation.

In 2010

he was

appointed

Poet

Laureate

of

Connecticut,

a

position

he held

until

2015. He

was a

draw in

the

poetry

circuit

and

could

draw

audiences

in the

hundreds,

and

sometimes

in the

thousands.

But, a

troublesome

heart

did him

in on

December

27th,

just

yesterday.

Lori and

Dick,

writers

both,

living

in a

house

barely

big

enough

for them

with

15,000

books,

inspired

one

another,

competed

gently

in their

way, and

became

bright

lights

separately

and

together.

No

matter

what one

might

say

about 78

years

being a

pretty

good

run, for

a

genuine

master

the

years

were far

too

short.

Carolyn

Raphael,

a fine

poet, an

old

friend

of

Allen’s,

and a

fellow

grandparent,

notes

that

“Dick

and I

exchanged

notes on

grandchildren

(He was

a valued

advisor

for

my recent

book, Grandma

Poems--Not

Too

Sweet.). In

this

year's

holiday

card, he

said,

‘This

doting

is quite

incredible

&

totally

unexpected..’

A wise

and

gentle

man....”

Expansive

movement

co-founder

Frederick

Turner,

the

former

English

expatriate

now a

dyed-in-the-wool

Texan,

remarks

that “In

my year

back in

England,

from

1984-5,

his

poems,

which he

sent

every

few

weeks,

were one

of the

things

that

decided

me to

come

back to

America.

I

admired

his

political

wisdom,

which

has

always

been for

me a

touchstone

of the

genuine

American

commonsense

tradition,

the

practical

wisdom

that

Tocqueville

celebrated.

Allen

did put

his

shoulder

to the

American

wheel,

with

tolerance,

decency,

and

principle.

And this

wisdom

makes a

space

for

beauty,

dream,

and

memory.

A joy

that one

can

trust,

not

based on

illusions

or

posturing....”

Wade

Newman,

a

long-time

friend

and

colleague,

remarks

that

“Dick

Allen’s

loss is

immeasurable

to the

world of

Poetry,

let

alone

his

family

and

friends.

He was

one of

the

stalwart

Guardians

of the

art form

of those

who came

before

him and

his

contemporaries.

His

integrity

as a

poet and

a person

can be

read in

carefully

crafted

poem

after

poem

throughout

his

lifetime.

His

highest

compliment

to a

fellow

poet, if

he read

something

he

liked,

was that

he

wished

he could

have

written

the same

poem or

that he

had

chosen

to

commit

it to

memory.

I can

boast

that I

own,

have

read,

and

cherish

each of

his

books,

and can

testify

that his

poems

only got

better

and

better

with

each new

volume.

I had

begun

reading

his Zen

Master

Poems

only a

few

weeks

before

his

passing,

and

finished

the last

poem

this

past

week

without

knowing

he was

departing.

The

book, a

meditative

masterpiece,

composed

over 20

years,

speaks

of

acceptance,

celebration,

and

wonder.

How

Long

Shall I

Wait

(excerpt)

from

Zen

Master

Poems,

by Dick

Allen

How long

shall I

wait

beside

this

small

lake

envying

the high

clouds?

The

passage

my life

opened

is

closing

soon.

How have

I walked

it?

"Dick

Allen

walked

it for a

long

time and

left us

a

wonderful

universe

of poems

to read,

reread,

and be

inspired

by."

Allen is

survived

by his

wife,

Lori;

their

daughter

Tanya,

of

Wallingford;

their

son,

Rich, of

Sayville,

N.Y.;

their

son-in-law,

William

Weir;

and

their

grandson,

Lincoln

Weir.

The

service

will be

held

Saturday

Jan. 6

at 2

p.m. at

St.

Paul's

Episcopal

Church

at 25

Church

St.,

Shelton

CT.

Arthur Mortensen

Expansive Poetry & Music Online

We Lose

Another

Friend

Poet

Daniel

Fernandez,

a good

friend

for many

years,

passed

away

on the

22nd

of June

at the

age of

79.

Friends

with

many

throughout

the

world

of poetry,

he published

in dozens

of

journals

and

magazines

and won

many

prizes

from

across

the

country.

Host of

the NY

Poetry

Forum

for

decades, Dan,

as he

preferred,

wrote

and

published

poetry

for more

than

sixty

years.

But the

story

few knew

lay in

his

somewhat

shrouded

past.

Daniel

was also

a

playwright.

And his

theater

was

composed

solely in

verse.

His

model

was not

Maxwell

Anderson,

the

best-known

playwright/poet

in

American

theater,

but

Racine,

the

great

classicist

of 17th

century

France.

And he

could

write,

and is

as good

a verse

dramatist

as has

ever

been

produced

in

American

theater.

In

rhyming

couplets,

he

managed

dialogue

with the

vivid

realism

of an

O’Neill,

but with

the

elegance

of a

classic

poet.

Alas,

only

scattered

audiences

on

school

and

library

tours

ever

heard

his

remarkable

Hamilton,

or his

Tupac

Amaro,

or his

Phaedre,

or any

of the

other

dozen or

so

plays.

Modern

directors

in

subsidy

and

commercial

theater

alike

have had

no

patience

for

verse

for

several

generations,

at least

outside

of

musicals,

shunning

such

work as

affected

.

Still, a

lot of

people

in

theaters

across

the

country

had read

his

manuscripts;

he sent

them

everywhere,

hoping

as we

all do

that

somebody

would

appreciate

the

work.

Hundreds

of

readings,

sitting

and

staged,

provided

memories

to many

friends

and

acquaintances.

A dear

friend

toured

with

Dan’s

Hamilton for a

year,

one

library

to the

next. It

wasn’t

the

Hamilton

we know

today of

course;

it was

however a

remarkable

history

play in

verse of

rare

quality.

His

sense of

theater,

developed

from

long study

and his

own

imagination,

was

enormously

enhanced

by his

long

marriage

to the

late

Carmen,

a

flamenco

dancer

who had

danced

with her

cousin,

the

great Pilar,

decades

ago.

I hope

someone

in the

family,

or among

friends,

will

make the

effort

to

conserve

the

manuscripts

of these

remarkable

works.

His two

books of

verse,

Apples

from

Hesperides,

released

decades

back,

and

Flight

Numbers,

which

Pivot

Press

released

a decade

ago,

along

with

many

published

poems in

journals

and

magazines,

are what

we can

still

directly

appreciate.

We

should,

and I

hope,

one day

soon,

see the

rest of

his

work.

Daniel

Fernandez

was

unique,

as an

artist

and as a

man. I

will

miss his

voice,

his

company,

his

fiercely

argumentative

spirit,

and his

unabashed

willingness

to speak

both

opinion

and

poetry

with

great

clarity

and

grace.

Burial

was on

July 3rd

in

Brooklyn.

On

September

2,

starting

at 2PM,

a

memorial

program

will be

conducted

by James

DeMartini

and the

New York

Poetry

Forum.

It will

be held

at

Soldiers,

Sailors,

Coast

Guard

and

Airmen's

Club at

283

Lexington

Avenue

in NYC.

Arthur Mortensen

Expansive Poetry & Music Online

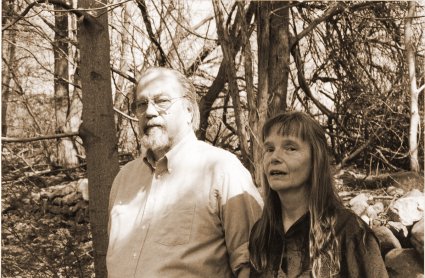

Photogaph:

Daniel

Fernandez

in Ft.

Tryon

Park,

1987

Flags as Symbols Flags as Symbols

Thoughts on an ongoing controversy.

For the generations that lived under them, now obsolete flags and imperial banners had genuine symbolic power. But, no matter an empire's skill at administrative sleight-of-hand or outright terror, how quickly one fades!

At the beginning of a century, the haunting trumpets of a triumphant return from a battlefield astonish thousands along a parade route. Sixty, seventy years later, within a lifetime, the center of government is an ash-filled ruin, the official statuary smashed by mobs, the fearsome armies disbanded, and, softly waving in a breeze, a new imperial banner instructs the populace of how time passes.

In the blink of an historical eyelash, what once symbolized fearsome power and domination disappears into a dusty room in a museum or is captured and hangs in an enemy's palace as a prize.

The following represented a variety of what were held by statesmen and poets as the final answers to political and military power in the ages their empires presided over. None still fly. More than a few writers have found poetry in this, including Keats in Ozymandias.

Roman Empire, Labarum banner of Emperor Constantine,

symbol of the Empire's conversion to Christianity.

He died 337AD. In a century or so, the western empire

was falling apart, and came under the domination of Vandals.

Austro-Hungary

It didn't have an official national flag, but its merchant ships bore this with its mark of crown and shield. It was also used as a battle flag until 1915. A few years later, at the end of World War I, the Austro Hungarian Empire collapsed.

Ottoman Empire

The thousand-year caliphate's last flag flew in 1923.

Spanish Empire, Cross of Burgundy Flag

Flown over Spanish colonies, from the early 1500s until 1785, when the empire began to disintegrate.

USSR -- Soviet Russian Empire

The greatest armed force in human history, a political system based on total control of an entire population. Its last flag was pulled down from the Kremlin on December 25, 1991,ending the Cold War and occupation of eastern Europe.

British Empire, Crown Colony of India

Flag pulled down after Ghandi's revolution in 1947. Enlightened as the British claimed to be, they were powerless before the revival of Indian nationalism. Over the next twenty years, the rest of the largest empire ever built split apart.

Empire of Japan

Ended after defeat in Second War War and new constitution of Japan, 1945-1947. Brilliant employment of arms on land and sea and in the air, as well as an astonishing will to employ cruelty and violence on defeated populations, could not stop its enemies.

China, Qing Dynasty

Perhaps the world's oldest organized society, at the end of the 19th century, it was disintegrating at every level, and then was swept away by war and revolution. Banner no longer used after 1890.

Portuguese Empire

A vast assembly of colonies until its collapse two hundred years ago, the worst of slave trading economies,one of the most oppressive regimes.

This banner was used in the Absolutist period. The Empire fell apart at the end of this, when it was no longer affordable -- 1816.

Byzantine Empire

The eastern remnant of the Roman Empire that outlived it by a thousand years; survived an errant crusade that turned from fighting Muslims to overunning Constantinople (modern Istanbul). This is the banner of Palaiologos Dynasty, used until the fall of Byzantium to an army of Moslems, 1453

Confederate States of America

A slave-centered, rebel republic that spun off from the United States in 1861. This flag was replaced with new designs twice before Richmond was overrun by U.S. Federal troops in April of 1865, 150 years ago.

Each of these vast domains was constructed on an overpowering foundation of one form of slavery or another, with the exception of Britain after 1848 and the post-Stalin USSR. Each empire has passed into history, its banners and flags now safely described as symbols of very little beyond what can be captured of their former authority in books. What otherwise, besides rot, happens to flags of extinct nations and empires? One fate is that of becoming an historical signpost. But, despite the former fame and ambit of what each represented, nowadays we may have to engage in a little scholarship to ferret out just what they stood for. What else? There's entertainment value

in

its use as a prop in an historical fiction for instance. There may be a possible moral lesson expressed by an old flag, thought that will have most likely been drawn from a successor empire. That's all there is. Dust to dust, as the saying goes.....

Well, maybe there is another value in an historic flag in use as funerary art. General Lee's battle flag (the Stars and Bars at the center of current conflicts over North American political history) is still used that way in some Civil War battlefield cemeteries (though less so recently). Mourning is a valid response to wartime death, obviously, and more Americans died in the Civil War than in any other conflict, but one has to look twice. Such commemorative art has genuine meaning only to those who remember (first or second hand) who and what it stands for. When that connection is lost, as late as a third generation, but more often, especially in America, within twenty years, what remains? It looks to this writer to be nostalgic fantasy (a prop for Civil War re-enacters, for instance) or as a propaganda tool to manipulate the ignorant.

By far the best way to appreciate such things, whether old funerary statues, or ancient flags of dead nations, is to note their fabulous irony, that, no matter how beautiful or how hideous, each flag stands for a dream that's been dead for centuries. Fortunately or not for all of us, time doesn't just pass; it erases. Dragging out old symbols to inspire fear or outrage should be left to politicians with a taste for losing elections.

Arthur Mortensen

Expansive Poetry & Music Online

Music and Verse

Music and Verse

Interview with Claudia Gary, with Philip Quinlan of

the UK's online poetry journal Angle, August 2014

From the online journal Angle in the UK: Claudia Gary on music and verse. The linkage between music and poetry, and how important it can be, is an ongoing discussion among poets, critics and readers. Gary's views on this are clear, well-founded and nicely presented here. Both as a composer and a poet, she presents a thesis with which one can agree or disagree. However, you won't find a basis for discussion, of course, unless you spend time investigating thoughts in the interview. Claudia Gary's published works includes Humor Me, from Wordtech Press, 2005. Claudia Gary, Wade Newman, and the late Alfred Dorn wrote the first four releases from the critically acclaimed Somers Rocks Press chapbook series (1996-2001, 22 titles in all). She has set numerous poems to music, including several by Frederick Turner. Attention to the rest of this terrific journal is strongly enouraged.

When the PDF appears, jump to page 79, where you'll find the interview. (It's not directly recorded in the table of contents.) There are links to performances of Gary's songs in the body of the interview. Don' t miss them. The essay she occasionally refers to by the late Richard Moore is in the old archives for EP&M. (See below)

Arthur Mortensen

Expansive Poetry and Music Online

Dark Energy

Dark Energy

Poems by Frederick Feirstein

Grolier Established Poets Series

Cambridge, Massachusetts

2013

74 pp., $17.95

The Expansive movement began decades ago to counter a depressing reality in published verse: most poems were lame efforts at self-mythification -- poor imitations of the first Confessionalists. It felt as though a tsunami of oatmeal had dimmed

poetry's most attractive facets, including prosody, strong diction, storytelling, and the use of reference and language clear enough to bridge the divide between individuals.

Stopping in at the now-extinct Gotham Bookstore to survey what was new, this writer too often spent more time looking at photos on the walls of what used to be than at current journals and new books. Hoping to find someone as engaging as, say, a Beat from the 1950s, or Eliot, Stevens or Millay from the 1930s, he found very little with real energy. Most poems and lyrics communicated mirror images of people this writer neither knew nor cared to meet, and in a style best described as the prevalence of sincerity over craft.

Then, at a bridge of lost hope, something emerged both old and new. Growing out of regional magazines like the Kenyon Review, this new poetry wave featured writers who knew how to use classical means to develop modern material. One of them, made visible by little presses called Countryman and Seagull, was Frederick Feirstein, a noted psychoanalyst in Manhattan

who'd once written for theater and television. What made his work jump off the page? The poems were alive; they told stories about someone else, and in a recognizable voice:

The

siren's screaming in my head again,

This time

it's Grandpa waiting to go down,

With his last preserves hooked up to his vein,

The sick king crumbling in his common gown.

Among the pots bubbling with grapes and plums

In his huge kitchen, we blow on tablespoons

Of juice, while Grandpa seals the vacuums

In the finished jars....

from

"Grandpa

Borea", The Survivors, 1974

The poet is not standing off at third person distance. This Grandfather is his; and, the wonder, shock, and horror at realizations about his

Grandfather's life (including his survival of the Holocaust), belong to the poet, as they should. Strong, symbolic figures are created that way, by who sees them, and how. When found in a mirror,

they're usually transmitted by the damaged and the deluded.

It's now forty years after that first, exciting book. Feirstein's shelf has grown long, and is one this reviewer often refers to. Some favorites include Manhattan Carnival, about to be re-released by Grolier; City Life, which includes the delicious comedy

"Psychiatrist at the Cocktail Party,"; Fathering; Ending the 20th Century, New and Selected; and Fallout. His newest, though hardly his last, as another book works toward publication, is Dark Energy, brought out by the Grolier Established Poet Series in Cambridge. The title is strongly related to a theoretical assumption of the same name in physics. A little quote about

"dark energy"from the NASA Web site:

More is unknown than is known. We know how much dark energy there is because we know how it affects the Universe's expansion. Other than that, it is a complete mystery. But it is an important mystery. It turns out that roughly 68% of the Universe is dark energy. Dark matter makes up about 27%. The rest - everything on Earth, everything ever observed with all of our instruments, all normal matter - adds up to less than 5% of the Universe. [Ed.'s bold] Come to think of it, maybe it shouldn't be called "normal" matter at all, since it is such a small fraction of the Universe.

--

"What Is Dark Energy?", NASA Science: Astrophysics:

http://science.nasa.gov/astrophysics/focus-areas/what-is-dark-energy/

Feirstein's a poet and psychoanalyst, not a physicist, but you can hardly miss the analogy. What we think of as our manifestation in the world, our behavior, acts, conversation, deeds, etc., is an incomplete picture. If we're able to negotiate growing up, career, family, and relationships with uninterrupted progress, we may never see what's missing. However, when something disturbs us without apparent cause, or makes a major part of our life narrative break up, we may go to someone like Frederick Feirstein. But most of the time, it's not that serious. We solve the problem by manufacturing a story or myth to satisfy our questions. That new piece of our narrative may not be real or complete, yet still reveal just enough to allow us to move on, assured that we know where we are on life's through line. Story and myth, insubstantial though they may seem, are arguably the dark energy of the human psyche. They drive us; they shape us; we can fall apart when they don't ring true. And that, in part, is the foundation on which Feirstein's Dark Energy is built.

We all tell stories that rationalize things otherwise not quite explainable. So do families, community groups, tribes, even whole nations. Here's an example of the latter. The tale of the Founding Fathers, for American Constitutionalists, is the story that justifies a concept of universal law that may otherwise be fairly regarded, as it was by Hannah Arendt, as a fiction. But, so long as the story holds, exemplary evidence attached, it has unmistakable power to change the way we think and act. Feminist stories about the Seneca Falls Convention, and its role in political emancipation of women, are just that; the facts can be interpreted differently. For instance, women were politically and economically emancipated first in the Wyoming territory (written about with some astonishment by European observers in the 1890s). One myth doesn't fit everyone. However, it seems clear that Seneca Falls is as strong a founding myth for some as Wyoming is for others.

We tell stories to comfort us in the night, to give solace during in the day. Stories translate shattering grief into manageable mourning. At a wake, or sitting shiva, we tell stories about the dead, proving not only that they once lived, but that we knew them and can speak about them. But we also have power to change the story, or tell a revelatory anecdote that nobody has ever heard before. Other stories create order in a world far too complicated and dangerous to face without a strategy. Stories and myths can help. We often depend upon them to do so:

Wheeling down Main Street in technicolor light

Are Disney's heroes, our mythology,

A comfort in the middle of the night.

Mickey Mouse, Minnie, Uncle Donald help.

The children of America are sick

Of war, cultural suicide, and greed.

Snow White, Bambi, Lady and the Tramp,

It's midnight now, help us in our hour of need.

"Gravity

of the

Black

Hole,

Prologue"

It's good to start an exploration like this with humor. While it may seem silly to ask cartoon characters for help, could they offer any? They're amusing fictions, fun to watch (as art and story), but -- and this is telling, they're also predictable. That makes them comforting. If you're really distressed when you start to watch one of these and end up laughing and feeling better, it looks like Mickey, et al, did something besides flit about on a screen. And there's more to it. Myths are prefigured stories. We know how each episode will turn out, whether it's set on Mt. Olympus or on a movie screen. We accept those conventions and, by doing that, we know how the complications will resolve. These restrictions on fictions also tell the stories' authors how to behave, so that we'll feel right about a retelling. And we can be nasty when someone violates that agreement. Look at the response to Ralph Bakshi's Fritz, the Cat (1968), regarded by many as pornography parading as a cartoon. Another critics described it as a wickedly funny variation on an old standby. We can't ignore the importance of this.

Myth creation, and storytelling, are vital to individual psychic health, and to whole societies. Colin Turnbull, in a controversial book, The Mountain People (1972), posited the theory that the Ik tribe of Uganda suffered complete social disintegration after a government-forced move from a rich valley to a near-desert. The change, according to Trumbull's account, undercut almost every social and cultural tradition the Ik observed, leaving a desolated people behind. Similar theories have been posited about the effect of the Bureau of Irish Affairs (or the American Bureau of Indian Affairs) by deliberate suppression of standard cultural stories, or myths, as well as local language. A large part of the Irish revival in the 20th century arose from poets reconstructing the great cultural myths of Eire. Much the same happened with the American Indian Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Cultural myths can take on a variety of forms, as this one from Vienna.

Freud found his myth in self-analysis

Where Orpheus, ne Oedipus he led

Us lost boys, naked, to our soul's abyss

-- To see in flashbacks what we missed in bed.

So ask yourselves, what myth became your Fate,

What traumas drew you in to play what part,

What self-deceptions, and what hypnoid states

Determined what exactly broke your heart.

"Gravity

of the

Black

Hole,

Myths"

(A note: don't expect extremely formal abstractions, academic obfuscation, or rarefied references from this poet. Thankfully he's not that kind of maker. The movement he co-founded all those years ago was strongly opposed to such tactics, describing them as means of avoiding, not delivering, meaning and story).

The sequence travels with Freud to the end of Part I, from the comforting, pre-war illusions of Vienna ("Daydreaming"), to the shock of the Nazis -- horrible confirmations of vital segments of Freud's perceptions and understandings, his story breaking toward scientific knowledge:

The mystic quest for light inside the dark

Witch's wood always is doomed to fail.

Heroic in our search for mother's milk,

We find poison in the Holy Grail

So we must cherish every nanosecond

And not turn Paradise into a hell --

Public in war, private in neurosis --

But live in every nonmalignant cell.

"Gravity

of the

Black

Hole"

A remarkable figure like Freud developed his stories toward a greater purpose, pushing toward a science of understanding variations of the human psyche. But the rest of us do the same thing, for similar (if more personal) purposes, as children do with fairytales.

In almost every fairytale we've ever heard

We children can't be seen, can't say a word,

And know our Fate must always be absurd.

For instance, when the father suffers grief

He sends us children to our stepmom's double

Who puts us on a cross or bas relief.

Our task, then, is to be resurrected

By challenging the unexpected,

To re-appear the fractally perfected.

Hansel and Gretel, Snow White are the best

To learn from. learn never to trust or rest

--The poorest of us and the wealthiest.

When we toast Life, remember we're Death's guest.

"Gravity

of the

Black

Hole,

Fairytales"

This is an important book, not only for the excellent poetic sequences, but for reminding us of a truth we can't safely ignore. Stories and myths stem as much from observation as from imagination. A good example is the apocryphal story about the best scientist making a difficult area of research suddenly visible. It sounds impossible; it's hard to prove, and can be misleading (failing to credit Rosalind Franklin is a very good counterargument about that story's plausibility). Still, we're surrounded by examples that are hard to ignore. Insoluble problems beset us and then, one day, thanks to Newton or Einstein or Freud or Feigenbaum, we go

"Ëœoh, that was easy.' And so we keep the myth in our repertoire of tools for understanding our world and our place in it. Feirstein offers something related, telling us what we should know about human storytelling and mythmaking.

We've always known that we make things up about people and the world. When we tell little fibs to cover up a mistake, most of us know what we're doing. We're papering a potential hurt with a (hopefully) harmless tale. But we don't talk about the process very much, or very honestly. And that's bad, because, with myth and exemplary story, when we forget what they can do, we turn them into sentimental mush. Then, the adults start texting while the movie's running and the kids wonder why they're being lied to. It happens a lot; it's a big part of commercial translation of popular culture.

To protect the children from the scariness of Little Red Riding Hood, right-thinkers turn the wolf into a nice creature who'd be a sweet doggie if he were fed more often. In the original, the message of the wolf was transparent: things are not what they seem. If you succumb to lies, even from someone who looks like your grandmother, you will be eaten alive by a world without tolerance for the ignorant. Scary -- but kids need those messages, not the squishy-soft versions written by committees looking to avoid liability. The stories and myths are not just warnings, but jumping off points from the illusory comforts of childhood. Feirstein does this especially well with wonderful variations on old stories, such as an aging Snow White (surely meaningful in American life):

Her face is now a zero of despair

Over aging, money, the fatality

Of menopause, sexual schemers...

She lifts a wisp of gray hair

And tries to grin,

"Bring

me no

more

dreamers."

"Snow White", from part 2., Gravity of the Black Hole

Or the Prince with his hope:

So here's Snow White, apparently not living.

Behind her glass, she doesn't look too well.

Yet the Prince has the innocence to hope

He can resuscitate her with this kiss he's giving.

Warmed by the fire in her inner hell,

He doesn't hear her cackle,

"Your breath's

smoke,"

Or see the Mother Witch inside her unforgiving,

Or the Victim shouting in the mirror,

"I can't cope!

This Prince here thinks I'm actually living?

"He doesn't know I'm happiest with dopes,

My seven ex's with their dwarfish living....

"The Prince", from part 2. Gravity of the Black Hole,

Ralph Bakshi never did better! And there's more to this. Common reference points make changing the story possible. The Prince and Snow White, older now, experienced, and in different circumstances, are still recognizable characters. The new stories build on the original, without which there would be nothing to work with. These variations, based on what students of chaotic systems call

"recursion", or

"re-entry," allow us to travel a familiar path, in the process of repetition gaining a different perspective, and sometimes a dramatically different outcome. Storytelling and mythmaking are how human beings build civilized perceptions of themselves and of their relationships to others. Some animals can talk. Some use tools. Some remember each other. And some can even predict the future a little. Human animals, through a luxury of intelligence, can construct enormous stories from anecdotes, original myths, carefully filtered experience. These stories are the framework on which we hang the canvas of our lives, whether as individuals or civilizations.

Feirstein develops this at some length in the opening sequence, "Gravity of the Black Hole", and its three parts are worth going back to again and again, for their wit, wisdom, and often dark humor. You'll never see Three Blind Mice in quite the same way again, or Cinderella:

The Prince with Cinderella was persistent.

Twice he lost her, twice he freed her from

Her own masochistic disasters,

And married her and lived forever after.

The Prince went twice to her crazy house,

Smoking cigars, riding on Fantasy,

Trusting himself, his courage; he knew he could

Rescue Love, rescue himself with Reason.

He knew he was the damned but favored son.

He married what's unconscious, what we shun.

Adults have different versions....

We've discussed the content but only implied the craft in Dark Energy. Reading these poems, with their delightful structure, intricate rhymes and supple flow, it should be no surprise that Feirstein has written lyrics for several full-length musicals. These poems, in their dramatic pitch, reveal Feirstein the playwright as well. The excerpts cited indicate that Feirstein has a terrific ear, with the sense to leave space for a reader (or listener) to fill in the blanks. That's a requirement in verse as much as in lyrics for a song. Versification got a bad name under the Modernists, hardly better under post-Modern critics. But, if you enjoy good songs, lyrics and poems, their success most often requires their author knowing what to do with prosody and how to fit the music. Feirstein figured that out a long time ago. Dark Energy is the latest example.

Reviews are not intended as survey courses for sophomores, but as teases to tempt readers to the bookstore, online or off. The rest of the book should be a surprise. You will be, not only by the reworked fairy tales and observations about them, but by Part II, the second sequence, "The Two Sides of the Moon."

Dark Energy is a remarkable book and is highly recommended. And special thanks to Ifeanyi Menkiti, who has not only started a fine new press but has also saved Grolier's of Cambridge, one of America's great bookstores.

To buy the book at Grolier's Bookstore in Cambridge, select the following: http://www.grolierpoetrybookshop.org/~shop/dark-energy/250089

It's also at Amazon and other outlets.

Arthur Mortensen

Expansive Poetry and Music Online

Arthur Mortensen is a playwright and a poet. His latest collection is Why Hamlet Waited So Long, from St. Sebastian Press. He has been the Webmaster for a very long time.

Omnibus Review:

Omnibus Review:

Broken Hierarchies - Geoffrey Hill;

Collected Poems -Michael O'Siadhail;

Collected Poems - Sean O'Brien;

Collected Poems - Paul Petrie;

Drysalter - Michael Symmons Roberts;

Dogwatch - R.S. Gwynn;

Walking In On People - Melissa Balmain

(All titles available at outlets such as Amazon.com. Sean O'Brien's Collected P:oems is a Kindle book on Amazon.com, but can be found in paper elsewhere.)

The New York Times Book Review has long been something of a sad joke played on the literary world, so I should not have nourished very high expectations for their recent special issue supposedly devoted to contemporary American poetry. Beside some pretentious posturing of less-than-insightful considerations of the value (or lack of same) of poetry in the contemporary world (William Logan, usually one of the few critical voices worthy of consistent trust and one of our best poets, is not enhanced by his company here), the NYTBR did actually review a few books"â€a very few, but multiple factors of their usual allotment. Given particular attention are books by James Franco, actor and degree-accumulator, and Patricia Lockwood, whose collection Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals, ponders such imponderables as:

"What if a deer did porn? Is America going down on Canada? What happens when Niagara Falls gets drunk at a wedding? Is it legal to marry a stuffed owl exhibit? What would Walt Whitman's tit-pics look like?" (I quote from promotional copy). The Times has reviewed the book not only in the Book Review but in the regular paper and profiled her in the magazine in the past month. Most poets would die for such coverage; obviously, they're not asking the right questions.

(Lockwood's is a bad book, but not as bad as I anticipated. She has a much better sense of humor and of the absurd than Sharon Olds. Parts of some of her poems actually display a certain amount of wit, but she is a one-trick pony and, like Frost's fireflies,

"can't sustain the part.")

But there have been books of poetry published over the past year or so that are worthy of close and continued and repeated attention, though they seem to have escaped the

Times' attention span. All should have much more consideration than I can give them here"â€and I could easily mention more"â€but if a few readers are directed to books they might otherwise have missed, my purpose is served. I also am going to include books by non-American poets; although I am ill at ease in a world ruled by multinational corporations whose claim to personhood grants them more rights than actual people, to we who are both blessed and cursed with an international language it seems parochial to restrict one's coverage to these shores.

Certainly the highlight has to be the publication of Geoffrey Hill's Broken Hierarchies (Oxford University Press). This is Hill's Collected and logs in at nearly 1000 pages, over 800 of them written since the mid 80s. Ludo and three of the collection of books Hill calls the Daybooks see book form for the first time; in addition, several other works, in particular Hymns to Our Lady of Chartres, have been substantially revised and expanded. This explosion of work, particularly since the mid-90s, has brought concern from a number of critics. Hill's poetry up through The Mystery of the Charity of Charles Pe"guy in 1983 emerged in small, tightly-knit collections spaced over gaps of several years. His work since has been much more expansive and tended to be freer in form, though much of the work in the past decade has returned to extraordinarily complex forms, some of which seem arbitrarily imposed over extended sequences.

I have been particularly wary of his triptych The Triumph of Love, Speech! Speech!, and The Orchards of Syon, which appeared between 1998 and 2002. Speech! Speech! I find especially troublesome, the effort it demands seems to result in diminishing returns. Hill's poetry has always demanded a great deal of effort, but it usually rewards it. The manner in these poems also appears a return to high Modernism; Hill has always been influenced by Modernism as a poet as well as being an insightful critic of it (Hill is one of our greatest living literary essayists), but I remain skeptical that its influence in these poems is benign for the most part.

These caveats are offered uneasily. Hill has been a difficult poet from the beginning and he takes no prisoners. I have read Broken Hierarchies in its entirely twice and the other collections that appeared previously many times. This is a volume that anyone who wants to know the poetry of the last fifty plus years has to come to some sort of terms with; the work of the past couple decades will take many critics more than a couple decades to come to terms with. With all my equivocations about the more recent work"â€and there is clearly greatness in it"â€just the work of Hill up through the Pe"guy would make him our greatest living poet.

Michael O'Siadhail is not a name much known in American poetry, but his Collected Poems (Bloodaxe) incorporates thirteen volumes and logs in at 800-plus pages. O' Siadhail is an uneven poet"â€he writes a great deal and individual poems can include a stinker of a line within a lovely passage. Many collections focus around particular themes: The Gossamer Wall is particularly interesting in how it deals with the Holocaust through a series of interconnected lyric and narrative poems. A Fragile City is heavily influenced by the ethics of Levinas. Yet he can also title a collection Rungs of Time which makes too much of a metaphor that certainly would be exhausted after a couple poems, rather than winding through an entire volume. His 2010 collection Tongues deals with etymological roots of words from an impressive array of languages (the poet is a linguist), but dozens and dozens of poems dealing with word origins pall after a bit. O'Siadhail has a Victorian expansiveness about him which can make him difficult to quote in snippets that would leave an appropriate impression of his work. But through the entire corpus of his work the poet's spirit is one of graciousness and, at his best, subtlety:

I feed on such courtesy.

These guests keep countenancing me.

Mine always mine. This complicity

Of faces, companions, breadbreakers.

You and you and you. My fragile city.

The overtones of

"countenancing" and

"complicity" add a further dimension to what is going on here. It would be welcome to have a good selected edition of O'Siadhail's work. His Collected can be a bit much to wade through at times, but there is much fine work here. The book comes with a CD of the poet reading nearly 40 of his poems.

Sean O'Brien's Collected Poems (Picador) weighs in at a bit less bulky 500 pages, consisting of nine collections plus an excerpt from his translation of Dante. Long identified with Newcastle, O'Brien is also a good practical critic. His Collected shows considerable range of themes and styles. His earlier books in particular demonstrate an energetic anapestic line:

They are bored with the half-life of scholarly myth,

Bored with the gaze of the sunblind student

Attacked by nausea on a bus to the Gut

Where adventure appears in a glass of anis

As a species of maritime fraud

At which the police can only smile

As they sit by the fountains comparing their guns.

There is a restless, searching quality to O'Brien's poetry, an urban poetry of decay, concerned with the city's hidden places. Trains and ghosts, and ghost trains, inhabit a number of poems, and we see the detritus of a post-industrial north, further ravaged by Thatcher, Blair & Co. O'Brien has a strong satirical sense; witness the beginning of

"Welcome, Major Poet!":

We have sat here in too many poetry readings

Wearing our liberal rictus and cursing our folly,

Watching the lightbulbs die and the curtains rot

And the last flies departing for Scunthorpe.

Forgive us. We know all about you.

His collection The Drowned Book was the first collection ever to win both the T.S. Eliot and the Forward Prizes (The feat has since been duplicated by John Burnside), so he has merited considerable attention in England, though his Collected has, surprisingly, not been widely reviewed. Although he is a very English poet in terms of reference, he clearly deserves more attention on this side of the pond.

Continuing with retrospective volumes, I want to call attention to Paul Petrie's Collected Poems. Petrie, who died in 2012, was my mentor and friend, and I can't pretend to much critical distance here, but this book holds the work of a lifetime successfully dedicated to poetry. The poems are not arranged chronologically; the ordering was carried out by the poet late in life. The subject matter is wide and the styles are varied; Paul would work the gamut of available forms. I cannot do better than quote X.J. Kennedy:

"When the best American poems of the Twentieth and Twenty-first Centuries are assembled, it won't matter who copped more prizes or was the subject of more dissertations. All that will matter will be the poems and whether people want to remember them. And then, if there is a just God in Heaven, or even if there isn't,

Paul

Petrie

will

have

some

poems in

there.

He did

so much

that

will

keep."

Amen.

Moving on to individual collections. I cannot think of a book in a long time that I've found more impressive than Drysalter (Cape) by Michael Symmons Roberts, the winner of the 2013 Forward Prize. Roberts' previous collections have been of interest, but Drysalter boosts Roberts into elite company here. The book is a series of 150 fifteen-line poems, matching the number of Psalms. Roberts seems to find about every available conceivable way to shape his fifteen lines; most long sequences tire and seem to demand selection. Not here. Roberts hits a high level from the first poem ("Small breaks first: cup on the marble floor, / mirror on staircase, cracked watch-face, / hairlines in roof tiles. Then it escalates.") to last ("So once again we walk and witness, / give thanks to the tangible and visible, / but no one dares to sing a note, dig in a heel.") There is a visionary quality to many of the poems"â€the beginning of

"The Sea Again":

has been among us in the night.

I knew it from the trace of grit,

beneath my feet, salt on my tongue-root.

The very last S of the backwash

filled my ears. Yet by dawn there is was

tame between the harbor walls.

Drysalter ranges widely over subject matter; it is unified by its sense of vision as well as the number of lines. It demands, and rewards, re-reading. Roberts has set the bar high and cleared it.

It has been far too long since R.S. Gwynn last published a full-length collection. The wait is now happily over with the publication of Dogwatch (Measure). The collection does not strike out in new directions, but the wry and witty perspective one and the consummate use of forms (particularly repeating forms) one associates with Gwynn are very much in evidence here. Literary take-offs frequently offer a good vantage point for the world's follies:

"A Darker Round" updates Dante to find room for plumbers, contractors, insurance claims adjustors and their ilk. I am glad to see

"Ballade Beginning with a Line by Robert Bly" (remember him?) in more permanent form and delighted in finding Larkin's Mr Bleaney reincarnated as

"Mr

Heaney":

"'This was Mr Heaney's room. The peat's / From off his boots. It got into the rug / And won't

be

Hoovered

out.

Likewise

the

sheets /

And

pillow

case"'" More seriously,

"On the Lea, April, 1621" is a poem that will last a long time, certainly one of the greatest fishing poems ever written. Making use of a shared pastime of two fishermen, who happened to be Izaak Walton and John Donne, the poem does not lend itself readily to being excerpted. A three-page poem written in heroic couplets, it unfolds gradually and with considerable grace. One couplet reads:

"Praise be to Him Who has provided much / To one of supple wrist and gentle touch." Suppleness and a gentle touch are certainly in evidence in this poem.

With her first full-length collection, Walking in on People (Able Muse), Melissa Balmain stakes her claim to membership among our best writers of light verse. Light verse is a misleading term. Most of Balmain's poems are not light in the sense of frivolous or superficial. They often raise serious topics, but they do so with a wonderful sense of humor. Children know poetry can be fun; that seems to be educated out of people quickly. And

"Walking

in on

People" is fun. The puns"â€that use of words condemned by writers of more substance than Shakespeare or Joyce"â€are wonderful.

"Hard-shelled" begins

"A noble urge to liberate the lobsters / came over me in Wal-Mart yesterday" but economics soon overcomes idealism. I quote

"Tale of a Relationship, in Four Parts" in its entirety:

"Kissing / Hissing / Dissing / Missing." Pretty simple? Try coming up with one yourself. Or maybe talk with a Gen-y-er:

"Come hang with me and all my bros-- / we'll grab some brews and Domino's / and Netflix The Avengers next. / Later, maybe we can sext." Fluffy doesn't like the family's new arrival:

"It can't climb up a tree, / it can't chase balls of string, / it leaves you zero time for me-- / just eat the wretched thing." And many, many more like these. If you are wanting to convert someone who thinks reading poetry is only a slight improvement over visiting the dentist, get him or her this book. Balmain is now editor of Light; I can't think of anyone better to carry on the tradition.

I don't intend this quick jaunt through the above to be in any way an exhaustive look at all the best that's been published in English-language poetry recently, or even a typical sampling (I only wish it were), but simply some of the work I have been most impressed with over the past year or so. It's not all the poetry that's fit to read, but more than one finds in the Times.http://www.expansivepoetryonline.com/ Robert Darling

Expansive Poetry and Music Online

July 30, 2014

Robert Darling, a noted and widely published poet and critic, is also an afficionado of Irish music, much of which he has shared with a grateful Webmaster, He has has been a professor for many years at Keuka College, in both the English department and the Fine Arts department..

Double Volume

from Wade Newman

East and West/

Final Terms

Poems by Wade Newman

Pivot Press

Brooklyn NY 11231

2013

123 & 75 pp., $15.00

Wade Newman's Final Terms / East and West is/are his first poetry collection(s) since Poisoned Apples, also from Pivot Press. The reason for the equivocation(s) is that the collections are published in one volume; when readers are finished with one compilation, they need merely flip the book over and begin the next, there being no back cover to the volume but two front covers. (I'm sure there is a technical term for the context, but my printing and research prowess fail me here.) Poor bookstore clerks must be confused as to how to shelve the book, but it is a boon to the reader, having two volumes for the price of one.

Regardless of the format, it is good to have more of Newman's work available for a wider readership. While he has won several awards and been widely published, this substantial collection more than doubles Newman's poems available in book form. East and West is the briefer of the two volumes and consists mainly of very short poems, heavily influenced by Japanese forms. Final Terms focuses more on Occidental forms, including many villanelles. The poems in both collections are dominated by love and love's mishaps and the motif of dance permeates both as well. Some of the women are mentioned in both collections as well; for the purposes of concision, I will therefore consider the books as one for the rest of this review"â€the reader should, however, keep in mind the collections are presented separately.

While a few of the villanelles lack repeating lines of sufficient interest, many are fine uses of a difficult form; in particular

"She Loves Me Less than Cigarettes" is wonderful, balancing the title line with the more positive

"After each pack, we have wild sex." And then there's the rueful

"Villanelle":

"There's

always a

woman

walking

out the

door /

They

exit the

same way

as the

one

before."

"Four Poems in the Spirit of Catullus" do a fine job of incarnating a contemporary Catullus: one could easily imagine him declaring

"No one's sexier when your temper's turned on" and delighting in such finery on his woman as

"the

spaghetti-strap

black

dress, /

Argentine

stiletto

heels, /

And

edible

underwear."

This brings us to another point: the poems in this book are overwhelmingly from a male perspective. One hopes we're past the time where this would be a problem for many readers. While there's no denying that a corrective was necessary, the commendable assertion of the female viewpoint should not render the comparable male one inappropriate. These poems, while strongly from a male viewpoint, should not be inaccessible to female readers. Doubtless, though, some will raise this complaint. Dogmatic readers will miss the playfulness of many of the lyrics. But that's their loss and not the fault of the poems.

Dance dominates many of these poems, several of which replicate the measures of a dance. Newman even offers special tango glossaries for the non-initiate. And one sometimes wonders whether the poet loves foreign women or their names more"â€he takes a great rhythmic delight in Uta, Yuri, Miwa, Nga, etc. Their names often merge marvelously with the dance steps and directions of the poem. It should be impossible for women so-named to be other than agile of foot.

The persona in many of these poems often seems as ill-starred in love as Larkin's; the women are often leaving, the speaker hears things second-hand ("Or at least that's what everyone says"), things are passing ("As each year I get older";

"The party was long over"), insults are endured ("I just crawl some hole and die"). But he keeps coming back for more and it is the dance that invigorates him.

There are poems of social comment, poems concerned about the craft of poetry, elegies and remembrances. But the overwhelming concern is with male-female relationships"â€several of the poems concerned with poetry end up addressing the muse as fickle lover. And this questioning and exploration of relationship is probably Newman's greatest strength, at least in these collections. And these lines at their best achieve a kind of simple profundity not easily captured. Consider the conclusion of

"Before":

Before we slept together,

I slept with you alone.

Before we loved forever,

I loved you in a poem.

This looks simple"â€until one tries to write it. There is not much in the way of verbal fireworks in this collection but a plain-spokenness enhanced by formal technique that is impressive. Final Terms/East and West deserves repeated reading. Much like Japanese ink drawings, the poems have an understated elegance.

http://www.expansivepoetryonline.com/ Robert Darling

Expansive Poetry and Music Online

May 14, 2014

Click here to purchase Wade Newman's Final Terms / East and West

Robert Darling, a noted and widely published poet and critic, has been a professor for many years at Keuka College.

Baudelaire Visited Anew by Helen Palma

Baudelaire Visited Anew by Helen Palma

Selected Poems from Baudelaire's

Les Fleurs du Mal

Translated by Helen Palma

Pivot Press

Brooklyn NY 11231

2014

88 pp., $15.00

Though the writer has enduring philosophical differences with Charles Baudelaire, I found in Helen Palma's translations many caverns of jewels: an urbane sensibility; an interest in vice; numerous sensual and aesthetic pleasures; symbols of sex and death; corruption; the macabre; sound and sense and beautiful color. I also found the difference between myself and the 19th century French poet: where I discover a hole in my jeans, I smile free and easy, at one with Huck Finn; when this Frenchman contemplates his thread-bare pantalon he damns all the world. So be it. What is under consideration are Helen Palma's superb translations, not my discomfort with the author of the originals!

A major difference touching translation is how the original language sounds. English is different in nature compared to French, not so much as consonant French to vowel-rich Italian, yet bold, practical English is not well-suited to the soft, subtle alliteration of the sweetly soothing, and effeminate, French dropping of vowels. With fewer bellowing vowels there is the opportunity for musical mellifluousness -- lush and Debussy-like. Palma evidently heard, for this lushness is well translated in

"The Sun":

And sometimes find the rhymes that died in dreams.

This life-giving father, and pallor's

foe"

I should mention that

"The Sun" is almost unique in this collection for the sincerity of its Romanticism. There is little of the picturesque decadence of the Symbolists; it betrays the poet's youthful optimism. I am reminded that Baudelaire's school chums recollected his writing-in and thinking-in verse. I can almost hear Blake.

Something

else of

French

that

Americans

find

unnatural

is the

cultural

obscenity

of the

gigantism

of

Rabelais' Gargantua, Lachaise's Standing Woman, and Beaudelaire's

"La Gante":

I'd probe at leisure her enormous limbs,

Climb up the slope of her tremendous knees;

And when

the

humid

sunlight

spread

disease"

"et cetera, although I cannot agree with the poet's point-of-view because I was never so young, never diseased, and never so French, yet, through Ms. Palma's translation, I can see what he saw in the manner that he sees. This is how translation is supposed to work.

And then, the rhyme: Here I found delight, word to word, line to line, stanza to stanza, and verse to verse. I found the rhymes fitting in almost every instance; accurate in translation, appropriate to the purpose, and telling in meaning. Most any verse would serve as an example. I choose

"Autumn Song" almost at random. The rhymes alone can tell the action of the drama:

dismal gloom / dreary boom

my soul / infernal pole

sacrifice / blood-red ice

log's descent / shall be rent

fearful throes / repeated blows

monstrous thud / fall's mud

for whom / with doom

Nowhere did I find that stretching after rhymes which is the sometime bane of translation. I found an ease, a rich variety of rhyme's application: in

"To a Passing Woman" couplets that dragged deep in lament to rise in the concluding couplet above the pallid skies; in

"My Beatrice" couplet after couplet of promise and fulfillment; and I expect that you will find meaning in many rhymes that I have overlooked.

Then, Ms. Palma is fastidious in her fealty to Baudelaire's peculiar adaptations of standard sonnet forms. Sometimes the rhyme scheme seems higgledy-piggledy, at other times to the purpose. A random reading of the 24 sonnets in this collection will surprise and delight. I choose the

"The Blind Man" for example of strophic structure, a division of what would be the final sestet divided with a turn between tercets (eef/ggf):

And thus they navigate unending Night,

Eternal Quiet's twin. While at your height,

O City, how you laugh and sing and roar!

Your lust for pleasure carries you astray,

And yes, me too; far more blunted than they,

I ask: What are those blind men looking for?

And then, there is an exemplary excellence in many of these sonnets which can be found in the final word of the final line: That fulfillment of the expectations of the preceding 139 syllables is found in

"The Cracked Bell" meaningfully and musically when the sound of the nail of the caesura

"dies." Yet, for me, the most rewarding of exits was found in

"The Setting of the Romantic Sun". Here is an ending, ending the ending: The end of the Romantic; the end of the sun; the end of the verse and of the song, a true sound sounding the fading echo of the clarion, ringing

"How splendid"" and ending

"cold snails." not so much a note as spittle on the reed.

In

"The Cask of Hate" I found the meter of feet, hearing the poet's heavy steps beating a bear-like rhythm. This heavy foot-fall makes substitutions all the more poignant, all the more telling: As is heard in the heavy step and squeezing of,

"Buckets

of blood

and

tears

squeezed

from the

dead"

followed later by the stumbling dactylic,

"Hate is the drunk in the depths of a dive";

concluding with the slow spondaic substitution of,

"To ever

fall

asleep

beneath

the

table."

Lovely. Another verse rich in knowing prosody is the first stanza of the first verse in this collection of translations,

"Spleen (IV)" where the slowing spondaic substitution and the descending drag of alliterations well meets the sound to the sense:

When the low, leaden sky weighs like a lid

Upon the mind that old vexations bite;

When the horizon in black bile lies hid,

And pours a dark day down, sadder than night"

This spleen is just that, not in good humor, yet it is skilled versification, demonstrating invention both in French creation and in English recreation. Another instance of rich prosody is found in

"From the Depths", a personalized Psalm 130. Do yourself a favor. Read this verse translation aloud, allow the sweet melodies to caress the tongue, the vibrations to message the throat, the invocations to seduce the ear. Here, the final quatrain of

"Hazy Sky" will deliver a taste of Ms. Palma's recreation of the French-like luxury in language:

Dangerous woman, with your changeling clime,

Shall I adore as well your frost and rime,

And learn to draw from that pitiless winter

Joys keener than its ice-and-steel-tipped splinter?

I found in this collection many invitations to participate in ethical corruption, much in the way that Shakespeare requests our participation in the corruptions of Richard III. In

"The Lid", Baudelaire would make us complicit in his stroking pleasures, the little sins against the cradle of his culture, which for myself I cannot do, yet I can and do find sympathy in the sound and in structure of the verse:

Go where we will, be it on land or sea,

Beneath a sun that's searing or cold-white,

As votaries of Christ or venery,

Possessed of millions or a widow's

mite"

Why accept the pleasure but deny the seduction? Because, in the actual virtue of structured verse, Baudelaire rejects the corruption of transitory phantasmagoria, as do I. I wonder if he knew? Perhaps I have dilated over much on the grotesqueries and the psycho-personal excesses. Even so, knowing something of biography, you may also be reminded that the poet during composition was enjoying syphilitic euphoria while suffering syphilitic agonies; that he and his mistress were soon to die of syphilis; and of that body of Symbolist art inspired by The Flowers of Evil (think the etchings of Baudelaire's friend, Flicien Rops).

But then, here the question concerns the skilled translations of Helen Palma, which surpass goodness, and deserve a reading. Buy and read this highly recommended book.

http://www.expansivepoetryonline.com/ Michael Curtis

Expansive Poetry and Music Online

March 14, 2014

Michael Curtis, of Arlington, is a well-known sculptor, architect and poet.For Ezra (Online Journal Of Translation) review of Palma's book click here (Don't be misled by page title. It's the Spring 2014 issue. You'll have to page through the poems to find the review)

-----------

To purchase Helen Palma's book, click here now.

Frederick Turner Review:

Frederick Turner Review:

The Gardens of Flora Baum

A Poem by Julia Budenz

(To read Turner's review at World Literature Today,

click on the photo or on the headline)

Kudos to Frederick Turner (author of poetic epics Genesis; The New World, and numerous critical works) and World Literature Today for this review of one of the major literary events of the still-new century, the late Julia Budenz's Gardens of Flora Baum, published posthumously by Carpathia Press, under the able direction of Emily Lyle and Roger Sinnott. This writer had the privilege of publishing a very small piece of this work in 2007 under the Pivot Press imprint. Five volumes long, a single, unified work, it is the poet's life's work, begun in the mid-60s, and left partially unfinished at her death in 2010. Read Turner's review, and then, to get your own copy, go to Carpathia Press, which offers the book in a gorgeous sewn edition (shown in Turner's own photograph), and in a more affordable paper version, which is also quite beautiful, its covers decorated with photos, including several of the poet.

A

New Harvest from Robert Darling A

New Harvest from Robert Darling

Gleanings

Poems by

Robert Darling

Foothills Publishing

Kanona, NY 14856

2013

92 pp., $16.00

Foothillspublishing.com

A poet, as the rest of us, runs a

constant race to stay ahead of

mortality's tsunami. The author

of Gleanings, with this

collection, sends a loud message

that he's still on the track.

Despite ailments in the last few

years that would flatten a

healthy bear, Darling is out

there. Of course, he's taller

than most, so his strides can be

long. And Gleanings is

one of those, a fine new

collection that steps along with

a delightful mix of craft,

humor, and wordplay. The latter

two have become rare in any

writing, and almost illegal in

poetry. But they are only part

of the overall mix.

Darling has always written with

great clarity, sometimes

mistaken for simplicity. As with

Tom Carper, a poet with whom

Darling shares strong traits,

what seems simple may be a lens

into deep water, as in the poem

"Undine."

There were the three of us: the water,

me wedded to the silent hills,

and, yearning back to water, her.

Strange now, the quiet of the house.

I move among possessions I

am doomed to always think are hers....

The risk with references to

mythology is that the author who

starts in a pond may find

himself in an ocean. Undine

(often spelled Ondine) has been

the subject of dozens of poems,

novels, films, operas, ballets

and even the Andy Warhol film

The Loves of Ondine.

Variations of Undine can be

found as characters in eight or

nine video games. And that's

just what's exposed by a casual

visit to Wikipedia. A more

interesting look at Undine came

from the iconoclastic Paracelsus

(17th century). Sometimes

described as the first modern

physician, he considered alchemy

not as magic but as a psychic

process, how one peeled away

presupposition and myth as

barriers to seeing things as

they are. His description of

Undines as female spirits in the

magical water of alchemy has to

be taken in that light to be

understood as anything but

medeaval fantasy. (see Carl

Gustav Jung's Alchemical

Studies (1967) for more on

Paracelsus). Darling's poem, in

its contrasting female and male

spirits, works the same theme

with considerable art. The lost

female lover, the male narrator

left onshore, despite precise

delineation, are given a

dimension by their conflation

with the Undine myth that turns

them into archetypes, the

Philosopher's Stone of

psychological analysis. A poem

of what may have been a personal

loss becomes terribly familiar.

And yet the poem works well

without knowing anything about

Undine.

Darling is a poet who likes to play

in many fields, as in "The

Abject Gardener."

My eggplant hatched some chickens,

My ginseng turned to scotch.

Primrose turned prurient

even while I watched....

The whole poem turns on

metaphors, puns, a slightly

sprung meter, and a basic hymn

rhyme scheme. As a linguistic

artifact, it's the kind that

political reviewers cite to beat

up poets they consider as

unserious. But for this writer,

this poem, and many others in

Gleanings, suggest a poet

with a strong grip on craft and

art. "The Abject Gardener"

through its art presents a funny

representation of how many

weekend gardeners see their

little box of nature. But it's

also about nature's joke on the

fellow who thinks he knows her

rules. One could go on but there

are only twenty lines to hoe.

A post-modern trick that's

probably used more in science

fiction than anywhere else is to

open with a long citation from

another author, not a pithy

quote, but a hundred or more

words, as in "Post-Modern Love."

In what will be a sonnet,

Darling starts with a long

quotation from Umberto Eco

regarding post-Modern

expressions of love. The

quotation is tendentious, the

sort of blather that makes this

writer reach for a baseball bat.

Darling takes the challenge he's

made to himself.

"I love you madly." His lack of irony

all too apparent to his lettered

belle.

"How can he mean," she thought, "what he

says to me

if Barbara Cartland, in each wretched

novel

has sprinkled her limp pages with

these words?"

She looked at him, her trembling

supplicant.

And then a line from Yeats occurred

to her:

We loved each other and were

ignorant...

As wonderful as it might have

been to show the entire poem,

that's illegal on a Web page

regulated by copyright

restrictions. Suffice it to say

it's one of the cleverest and

funniest sendups of academic

theorizing this writer has read

in a long time.

A central problem to a poet of

recent generations is the

demystifcation of nature. With

the astonishingly rapid

development of science, lots of

easy metaphors went into the

trash. In a world dominated by

science, a lot of comparison is

not so much hackneyed as it is

idiotic. The modern attitude is

best expressed by Mark Twain in

Life on the Mississippi

when he notes (in paraphrase)

that he'd rather know why the

sun shines than write a metaphor

about light. Darling looks at

this still controversial notion

in "The Geese".

An arrowhead without a shaft,

impelled by instinct's sure

return,

aimed at a target, north and

south,

geese narrow over altered land.

They'll have to do for myth.

These woods

were dispossessed by pious folk

who cleansed the savage with

the Word....

Pond to ocean again -- the

dispossession of magic from the

world by science has not been an

altogether clean process.

Indeed, it's fair to consider

demystication as the original

sin of modernity, as the British

Bureau of Irish Affairs, or the

American Bureau of Indian

Affairs, both run by the

Puritan's intent on removing the

"wrong" magic from their

subjects. The poem's resonance

is not just with the logical

positivism derived from science,

but with the arrogation of

authority by yet another way of

seeing things only one way. This

won't make anyone on either the

Left or the Right very happy,

and probably not many in the

sciences either, which is why

it's such a terrific poem,

reminding me of A.D. Hope's

"Standardization," which looks

at another clash of perceptions.

Darling manages this quite

differently, however. The

strongest trait Darling shares

with Maine's Tom Carper is a

deceptively simple diction. The

Australian poet (Hope), on the

other hand, could often strike a

reader as speaking from Olympic

heights, which is not always an

advantage with contemporaries.

Further, on the theme Darling

opens, not only is clarity

required, but a trace of

humility and more than a little

regret, as in his final

characterization of the geese:

Poor one note Sirens whose

crude calls

no one will follow but the

seasons...

"The Geese" is a brilliant poem

in a brilliant collection.

Gleanings is a book to

spend some time exploring. The

poet is a gifted prosodist (his

uses of assonance and consonance

deserve another review -- he is

master of both). Darling does

not write especially long poems,

but each needs careful reading,

the first time for enjoyment,

the second to catch what you

missed, the third to enjoy

again, etc. Poetry collections

aren't airport novels.