Fred Feirstein

Expansive Poetry & Music Online Review

Ending the Twentieth Century

by Frederick Feirstein

review by Arthur Mortensen

review by Arthur Mortensen

Fred Feirstein's sequences, of which there are two superb examples in this book, remind us of what we nearly lost in the long academic obsession with confessional poetry. We nearly lost what we find in Feirstein's narratives: character; coherent story; historical context; location; and all those details of life external to the author's private thoughts that make poetry worth reading, nearly sacrificed on the altars of Modernism and post-Modernism, whose high priests presumed the telling of stories outside one's self to be not possible. Maybe they should read Manhattan Elegy, the superb opening of this book. Lose character, place and detail and what's left?

Jump outside of poetry for a moment and imagine Paths of Glory, Stanley Kubrick's picture of the First World war. Take away the portraits of corrupt general officers, of the four young men condemned to die, of the colonel caught in the middle of a conspiracy. Take away the precisely observed life and death of trench warfare. Take away the enlisted men's club where Dietrich sang. Take away the refined insulation of the officers' club. What's left?

Of course nothing is left. Yet for a long time after the Second World War, particularly since the late 1960's, critics and poets alike in America have debunked what is interesting in narratives, rationalizing that by saying that the storyteller's choices are only personal or political preferences, thus giving the lie to the narrator's claim to be able to tell a story outside of his or her own prejudices. What bunk! Of course authors pick according to their preferences; so do all human beings. Where there is a conjunction of an author's preferences with those of other people, an author gets an audience, and, if that conjunction lasts or reoccurs later on, the author will come back into fashion. So what? This is news?

Frederick Feirstein has wondered about that kind of intellectual sleight-of-hand for decades, written essays about it, demonstrated on behalf of different directions he felt were right, but his most significant action was to be one of the founders of the Expansive poetry movement, which for the last 20 years has been the most exciting source of poetry in America. For, in joining that cause, Feirstein bucked theory and went to work as a poet. The results, both here, and in his other books, are strong stories, vivid characters, and unforgettable locations, all conveyed with a poetic art as good as anyone in his generation. They began noticeably when he was thirty-two.

Feirstein would have none of the Modernist denial of narrative then, in writing the Rabelaisian Manhattan Carnival (and in rhyming, iambic pentameter couplets that sound as "American" as anything by W.C. Williams) anymore than he would in this book's lead sequence, written twenty years later, and what a fine sequence Manhattan Elegy and Other Goodbyes is.

"The past is like a library after dark

Where we sit on the steps trading stories

With characters we imagined ourselves to be."

from Manhattan Elegy

These first lines, from Manhattan Elegy, the first of this 24-poem sequence, could be a credo for Feirstein who, as a poet, playwright and screenwriter, is more informed by his work and experience than by literary theory. And, not surprisingly, these are poems about lives in perspective, beginning with an elegy, a melancoly reflection on a world that no longer is, a world so much the narrator's that he has difficulties imagining that it has disappeared. Such beginnings are treacherous; we could be in for the usual nostalgia. Such is not Feirstein's intent. Sometimes, while the old days were no great shakes, they were better in the sense that we could have gone in a different direction than we did. And what time better fits that in America than the 1950's?

"When we were young and and optimistic, rich In time, Main Street, U.S.A. seemed poor in soul. Its rows of churchly, gingerbread houses, Clichés slept and fed, bored a poet Who wanted us cynical as Paris With its wise Sartre and sexy Signoret Sitting in raincoats in Les Deux Magots While a knowing Piaf number played. from The Magic Kingdom

Feirstein might seem to be taking us into a standard contemporary story of how changing the bad old ways led us toward the promised land. Of course it didn't. With much the same motivation for policy decisions as for those in art and literature, that the great middle in America was too ignorant and too staid to be trusted with consequential acts, we plunged into the miserable management of an empire, with the concomitant destruction of democratic institutions, imperial war, and "the assassination of hope," a quality of government and corporate policy that is just as evident in nihilist literary criticism and increasingly artless poetry, as if becoming like the perceived problem would somehow overcome it. Feirstein didn't miss that point, nor that of the real reasons people came to Manhattan, to America, reasons born of hope, not cynical resignation:

"Out of the shtetl, out of the pogrom (My mother whimpering till America) My son, nine, sits among macaws and hibiscus At a white piano bar, handsome As a movie star, smart as a physicist, Ignorant (my doing) of his heritage.

Heritage -- something to scorn, yes? What we throw in the trash before roller blading to work through crowds of fearful pedestrians -- Feirstein knows such thinking is poisonous. Out of heritage, not only its good but its bad lessons, hope emerges. And, whether hope is seen as a perpetually vanishing carrot held out to a reluctant ass, or as the light that leads us out of the darkness of oppression, such poets as Feirstein know by experience that it's a lot better to believe in a better future than mope about the latest vision of doom. He conveys this with superior competence in prosody.

He has a lot in his playbook as a poet. He mixes popular imagery, whether from rock 'n roll or Walt Disney, with plain style storytelling, historical reference, a gift for dialogue, philosophical observation, and as sharp an eye for character as you're likely to get in a contemporary writer. He scores time after time, as in this depiction of a World War II fighter pilot contemplating the present and the past:

"...'You can only feel shame Where there are people around you who care'... He lives above a shooting gallery. He points To the barred window with an American flag And gives me the Latin names for all his flowerpots. 'I would like to invite you in,' he says. 'But it's sunset, and this is the war zone. Can we meet tomorrow in traffic, You bring the questions, I'll bring the lunch?' 'Yes, sir,' I say, and he salutes me. I cross each avenue as if it is A border. My wife greets me at the door, A stricken look on her face." from War Zone

But doesn't concentration on content fly in the face of contemporary theory, which is all wrapped up in analysis of surfaces, whether in the line by line "interpretation" of some critics, or in the post-Modern assumption that a unique surface is the only valid aspect of a work of art? Certainly it does, but why else do people tell stories but to convey what happened, where, to whom, and what the consequences were? All the affectations of film's Quentin Tarrantino (or of his predecessor Orson Welles) to the contrary, most people want narratives to take them somewhere they haven't been before, even in a thousand-round-a-minute variation on The Terminator, and to be given details, incidents, and actions that are plausible within the confines of characterization and of the overall context of the story. Audiences may not voice that on opinion cards (they're rarely given the chance to), but the market, whether in the stories conveyed by movies or by poets, has a way of winnowing out material favored by the affected and the bored.

Some of such material concentrates on the idea that narratives are only "about" the way they're told, as if the actual stories were only something that concerned the Phillistine mob sacking the libraries and keeping business hot in the porno shops. Of course the actual stories are highly significant to audiences (perhaps why they're held in such contempt by many writers and critics). However, acknowledging that the quality of a surface is at least a guide to the rest, be assured that Feirstein has fine technique. A poet with all the tools, Feirstein employs meter, rhyme schemes (note the one in Celebrating, as complicated as any in Wordsworth), regular stanzas, and, using his ear as a playwright, creates work that sounds wonderful out loud. He dares to be coherent, even about subjects that are lacking in logic, and by doing so spits in the face of poetic fashion. He is, in short, highly capable of using a poet's instrument. But he doesn't find this skill a means to its own end; it is instead a means to tell the story, just as Singer's gifts in prose were a means to tell his wry fables. How else would Feirstein achieve his aims of conveying such rich content if he weren't competent at surfaces?

Perhaps the Modernist and Post-Modernist critics have it backwards; perhaps the quality of a work of art's surface is an indication of competence, while the conveyance of content is an indication of high art. Frederick Feirstein shows in this book how a high level of competence in prosody, combined with rich, evocative, and well thought out content, can result in poetry of rare art. This book is highly recommended.

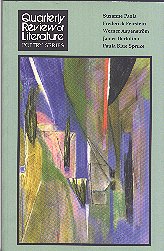

Publisher Information (Ending the Twentieth Century is published in The Quarterly Review of Literature Poetry Series, Volume XXXIV, $12.00, includes Glass by Suzanne Paola, Selected Poems by Werner Aspenstrom (translated from the Swedish by Robert Fulton), Snail River by James Bertolino, and Katsina by Paula Blue Spruce) QRL 26 Haslet Avenue Princeton, NJ 08540 Editors: T&R Weiss

Quarterly Review of Literature # XXXIV

Ending the 20th Century (QRM, 1995)

(Amazon)

Quarterly Review of Literature

1995

City Life (Story Line Press, 1991)

(Amazon) (including the The Psychiatrist at the Cocktail Party)

Story Line Press

1991

Return to Q&L/Musings Online home page.