|

REFLECTIONS ON SALLY COOK

___________________________________

SUSAN JARVIS BRYANT I have known Sally Cook

since 2019. I will always be grateful for our friendship, her lessons in

life, and in poetry – poetry that has a unique, synesthetic voice that

delights the senses and sings to the heart. Sally has left a beautiful

trail of artistic wonder in her wake, and it is an honor to have known

her. LESSONS

FROM THE

BEST

She summoned scenes in

swirls of luscious hues – Her magic kissed the canvas

and the page

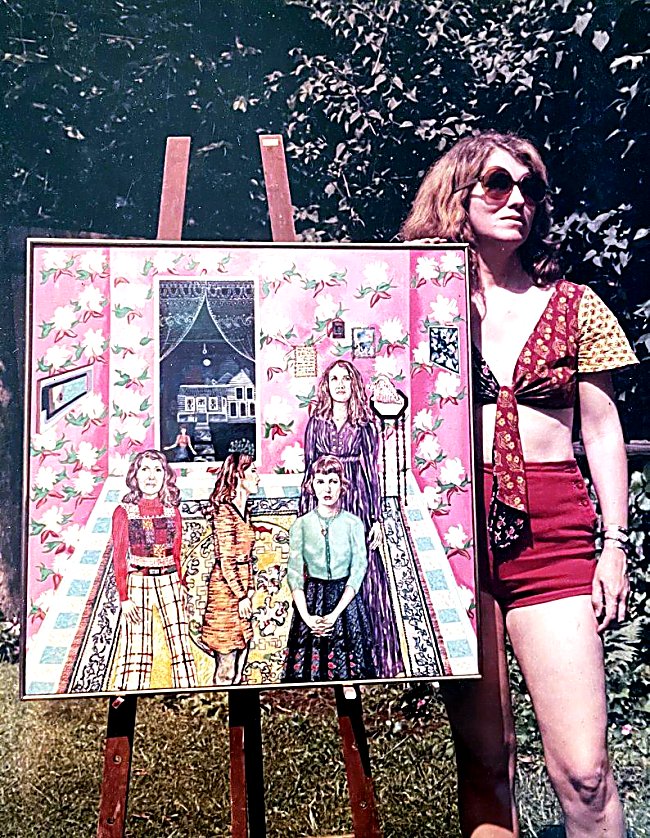

JOSEPH S. SALEMI IN MEMORY OF SALLY COOK I knew Sally Cook for over twenty years, even though we never met in person. All our communications were through letters, e-mail, or the phone. Around the turn of this century she had gotten my address from another poet, and had written to me out of the blue, asking if it would be alright if she sent me some of her poems to examine and comment on. I had received such letters from poets in the past, and had always managed to refuse politely. But there was something different about Sally’s first letter. She showed a sophisticated command of English prose style, and her straightforward, confident character was reflected in every sentence. She mentioned her long career as a painter, and even discussed some of the details of her upbringing. Every word of that long letter seemed to present a definite personality: one that was intelligent, perceptive, fully in command of language, and very self-aware. There was complete honesty in her letter, and absolutely no pretentiousness. It was also quite revelatory, much like a letter from the nineteenth century that mirrored the entire thought and feeling of the writer. I wrote back at once and urged her to send me some of her poetry. When it came, I was not disappointed. The poems were strikingly original and interesting. Some were personal, others observational, and many others had as subjects individuals whom Sally had known over the years, particularly family members. She had a very close relationship with her mother (Berenice Stone Cook) and her paternal grandmother (Maude Cook). On the other hand, she had a fraught and distant relationship with her father Donald, and with her only sibling, a sister. Many of these personal poems dealt with actual incidents in her childhood or teenage years—some comic, some ecstatic, and some upsetting or even painful. What I noticed was that Sally often became attached to someone who was a teacher or mentor or advisor, in connection to whatever she was studying—and she studied quite a bit. It could be music, painting, literature, arts and crafts, antiques, gardening, religious thought, or a dozen other subjects. She had an omnivorous interest in many areas. The need for an advisor or mentor seemed to be her response to the coldness of her father Donald, whom she never seemed to be able to please. Whether in painting or in music or in poetry, Sally always spoke of the importance of synaesthesia. She strongly felt, as far back as her early childhood, that colors and sounds and words were interchangeable and parallel. She could paint a sound, or hear a color, or mentally visualize the sound and color of any word. Every chromatic or acoustic phenomenon was for her a living personality, as real as an actual human being. Much of this perception was certainly due to the ferocious at-home training that she received from her mother and grandmother, involving endless lessons and hours of practice at the piano, and constant drilling in the meaning of new words. I was always amazed at the range of Sally’s diction as a poet, which went far beyond that of most contemporary practitioners. Music and writing she learned from those two fierce teachers, her mom and her grandma. But drawing and painting was her own choice and specialization as a young girl. She once told me that her mother Berenice and her grandmother Maude had drilled her to exhaustion, and she learned to play music and to write words in the same way that soldiers learn about weapons from drill instructors. But drawing she did on her own, as her personal escape from that training, and as a delightful relaxation. She drew in her school texts, her notebooks, or on any scrap of paper she could find. Drawing and painting became so great a force in her young life that eventually her father relented in his opposition, and paid for her attendance at an art school. She loved to paint, and had excellent teachers who guided and encouraged her. One of them insisted that she go to Greenwich Village in New York City, and hang out with the Tenth Street crowd, a mixed group of artists (some of them Abstract Expressionists). This was in the early 1950s, when the Village was a hotbed of artistic endeavor and experimentation. Sally was a lovely and highly talented young woman, and eager to be a part of this scene. She did some excellent work in the abstract mode, but she quickly came to dislike the Tenth Street group, which was dominated by arrogant, careerist, macho male artists who did not take female work seriously, and who displayed too many of the male chauvinist traits that were condemned by later feminists. So she left after a while, and returned to upstate New York, where she was born and raised. It was there that Sally Cook came into her own as a major painter. She continued in the Abstract Expressionist style on occasion, but more and more she began to paint in a manner that hearkened back to the unusual small sketches of imaginary fancies that she had drawn in her girlhood. The use of the phrase “magical realism” to describe her mature work is borrowed from literary criticism, where it refers to a certain amalgamation of the real and the mystical in the novels of Márquez and Borges. But Sally’s work escapes that category. When she painted a scene, the entire thing was otherworldly and dreamlike. Like Frida Kahlo, she often included images of herself in a painting, or else of other persons whom she knew or remembered. Her titles to her paintings were sometimes lengthy, as if serving as a kind of key or epigrammatic hint to reveal the canvas’s deepest meaning. Sally also had the habit of painting on the frame of a picture, including it in what might be called a totalizing unity. She made the frame ornamental rather than a continuation of the subject on the canvas, but when all was done, the frame was inseparable from the canvas in an aesthetic sense. It was a part of the entire visual experience. Her work slowly gained a loyal base of collectors, supporters, and a few galleries. Some museums bought her work. She had some shows (not enough, to be sure), but she was not part of any trendy movement in the 1960s, a time when the artworld became more of an esoteric joke at best, or a sleazy investment racket at the worst. Sally continued to paint in the ways that she felt comfortable with, and that satisfied the demands of her interior audience. She came to poetry late in life. But when I saw those early poems that she mailed me, I knew she would soon be a major talent. Without any training in meter or rhetoric, other than what she had picked up by reading the masters, she had managed to write excellently measured lines, and make use of all the standard tropes and figures. I coached her in a few things, but there was nothing that she did not pick up in a flash (probably the result of that strict early regimen of Berenice and Maude). I recall that she did have some problems with punctuation at first, but after I had corrected a few of her poems in this area, she was as sound as a bell. We began a correspondence that continued, on and off, for many years. She would sometimes send me a first draft, asking for advice as how to develop it fruitfully. As time passed and her work became highly polished, she would send me her final copy, and all I would do was add a suggestion or two for improvement. And finally it reached the point where she would send me her finished piece, and I would simply call her up and tell her that it was impeccable. We never met. There was no way I could journey to a far-off corner of upstate New York called Silver Creek, nor could she at her age make a trip down to Brooklyn. But our friendship became very real, even if it existed only by means of letter or telephone. I also came to know her husband, Robert Fisk, an extremely talented illustrator and cartoonist. Sally and Bob were very close, and whenever she sent me an envelope with her work in it, Bob would lavishly decorate the mailing envelope with playful and whimsical drawings, or else include a letter of his own to me. He also did perfect calligraphy for my address. I always knew immediately when a communication from them arrived! I told her to submit her finished poems to magazines (and later on, to the online websites that started to replace printed mags). Her work was accepted quickly, as it stood out from the free-verse sludge the usually inundates the editorial offices of poetry venues. This was just about the time of the temporary triumph of New Formalism, so there were opportunities for metrical and rhyming poets that did not exist earlier. Her work appeared in several journals, but her most extensive online appearances were in Leo Yankevich’s The Pennsylvania Review, Arthur Mortensen’s Expansive Poetry Online, and Evan Mantyk’s Society of Classical Poets. I sometimes advised her to write more poems on non-personal subjects, and she did so. She loved Emily Dickinson and Henry James, and wrote excellent poems about them. Her comic poem “Mates of the Greats” is a delighrful jeu d’esprit about the marital or sexual relationships of various famous persons from the past. But I realized that her real strength as a poet lay in meditation on incidents from her childhood and upbringing, or from life experiences in upstate New York. She was the most evocative when these were her themes. Sally Cook came from old Anglo-Saxon stock. She could trace her lineage as far back as Geoffrey of Anjou, and the Plantagenet kings. She was a proud member of the D.A.R. and other patriotic organizations. Her viewpoints on political and cultural issues (like her husband’s) were strongly conservative, and these were a negative factor when they came to the attention of others, and spoiled some of her chances for publication. In addition, her close friendship with me was widely known, and this also worked against her being accepted in the po-biz world. As a tart-tongued right-wing reactionary, I have always been poison in that community, and some of the enmity against me rubbed off on poor Sally. Guilt by association is a living reality for left-liberal Wokesters, and they use it all the time. But Sally Cook didn’t care. Like all true artists she was basically indifferent to public response to her work. She knew that her work was good, and that’s all that mattered. There is another truth about Sally Cook that deserves mention. She was a psychically gifted person. She had an uncanny ability to read minds, to intuit hidden facts, and to be aware of health problems in persons to whom she was close, even when they were absent. She also experienced a large share of naturally inexplicable events, usually connected with her mother but sometimes with others. These experiences made me think of Sally as a medium, a sorceress, a shaman, and an enchantress in the style of the medieval Morgan Le Fay, or the poet Yeats’s wife, Georgie Hyde-Lees. Some of the experiences she told me of were clear instances of the paranormal—not trivial things, but events that involved palpable and undeniable physical activity. She was intimately connected with a netherworld of spirits, occult forces, and the beyond. Unlike most people, she was not frightened by any of these things, but merely took them as part of the way the universe worked. I told her, and I told others, that she was probably the best formalist poet writing today. I don’t know all of the formalist and metric poets who exist, but I know many of them or their work. They have different strengths and skills, but not one ever struck me as having the overall competence and sheer poetic force of Sally Cook. Albert Jay Nock once asked how one could tell if one were living in a Dark Age. There are many possible answers to that question, but to my mind the best answer is this: If a poet with the verbal polish and perceptive insight of Sally Cook can be ignored by the Poetry Establishment, then the darkness we are in is truly stygian. I have lost a close friend, and a fellow poet with whom I shared a strong and sympathetic relation. But the world has lost a voice of elegant beauty and precision, of verbal accomplishment and fine perception. If we must weep, let us weep both for Sally Cook, and for all those gifts. May the earth rest lightly upon her.

Sally Cook Poems On Expansive Poetry Online

Expansive Poetry Online

|